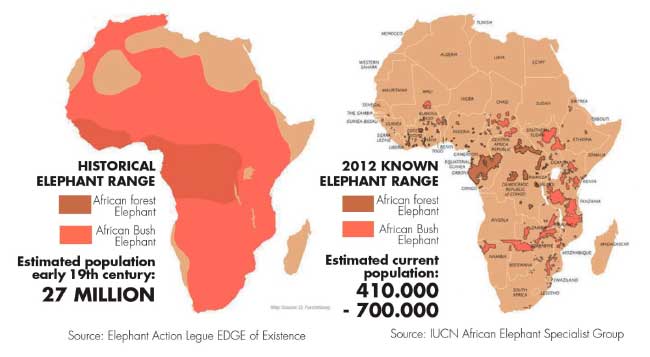

Unfortunately population numbers of all elephant species continue to decline in the wild. Human encroachment, habitat loss through human population growth and infrastructure development, and poaching pose major threats. Conflicts between elephants and humans are increasingly frequent due to human population growth causing a decrease in suitable habitat for elephants. As elephants seek food and water in historical elephant habitat now converted to farmlands, humans attempt to protect their lands and livelihoods and human and elephant injuries and fatalities are often the result.

There are three distinct species of elephants: the African savannah elephant (Loxodonta africana), the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), and the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus).

The African savannah elephant is the largest land mammal with the Asian elephant coming in as a close second and the African forest elephant the smallest of the elephant species. They are all generally similar in appearance.

- Males are larger than females.

- Both sexes continue to grow throughout their entire lives.

- All species of elephant have trunks which is an elongated nose and the upper lip combined.

- The elephant uses its trunk to breathe, explore its environment, communicate to and about conspecifics, pick up, push, carry, and to drink water or give itself a shower of water, mud, or dirt.

- Its trunk is essential to the survival of the elephant although a few elephants have been able to successfully learn to use their trunks after severe injuries caused by wire snares set by illegal hunters.

- The feet of all species of elephants are round with a large circumference in relation to the legs. The elephant’s weight rests on a pad, which cushions the toes. This pad grows continuously and is worn down by the natural movement of the elephant.

- In recent years, a significant amount of information regarding the social structure of wild elephants has been published. This information has painted a fairly complete picture of the social nature of the African Savannah elephant. Significantly less information is available about the African forest elephant and the Asian elephant as their social behavior is much more difficult to observe due to smaller populations sizes and their habitat of dense forests. Based on existing data, all female elephants are social animals spending much of their time rearing calves. Male elephants leave the family as they enter their teenage years. Males, once separated from the natal group, will form loose associations with other bulls except while in musth, at which time they are solitary. Adult males spend the majority of their time away from females except during breeding opportunities.

Africa

Elephants once ranged throughout Africa. By the Middle Ages, the species became extinct in northern Africa primarily due to the ivory trade. Controlled hunting, a drop in the price of ivory, and the development of wildlife preserves following World War I saw the population of elephants once again increase within Africa.

In the 1970s, the increase in the price of ivory reignited the poaching of elephants. The population, estimated to be at about 1.3 million in the early 1970s, dropped by more than half by 1995.

Asia

The Asian elephant once ranged from the Tigris-Euphrates in western Asia, east through Iran and south of the Himalayas, throughout south and southeast Asia including the islands of Sri Lanka, Sumatra and Borneo, and into mainland China northwards at least as far as the Changkiang (Yangtze river).

Elephants have disappeared entirely from western Asia, Iran, and most of China. They currently occur in the following regions and countries although they are usually restricted to hilly and mountainous areas: a) Indian subcontinent: India, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh, b) Continental southeast Asia: China, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and Malaysia, c) Island Asia: Andaman Islands (India), Sri Lanka, Sumatra (Indonesia), and Borneo (Malaysia and Indonesia) (Sukumar 1994).

It is estimated that at the turn of the century there were more than 100,000 elephants in Asia (Santiapillai and Ramono 1992). The surviving population of Asian elephants is estimated between 30,000–50,000, or one-tenth of the population of both species of African elephants. The actual number of elephants found in the wild then and now can be only rough estimates.

The process of trying to systematically census the densely forested regions of Asia is extremely difficult. In many countries, unfavorable political conditions hamper or prevent census work.

Elephants have many unique physiological characteristics.

Here are just a few!

Ears

African Elephant - Ears

Asian Elephant - Ears

Generally, the size of the ears is directly related to the amount of heat dissipated through them. The difference in ear size between African and Asian elephants can be based on their geographic range. The African elephant usually lives in a hotter, sunnier climate than the Asian elephant and needs larger ears to aid in thermoregulation.

Although ears help to regulate body temperature in both species, they are more effective in African elephants in that regard because the ears are larger. Flapping the ears helps to cool an elephant in two ways. In addition to enabling the ears to act as a fan and move air over the rest of the elephant’s body, flapping also cools the blood as it circulates through the veins in the ears. As the cooler blood re-circulates through the elephant’s body, the animal’s core temperature will decrease several degrees.

The hotter it is the faster the elephants will flap its ears. On a windy day, however, an elephant may find it easier to simply stand facing into the wind and hold its ears outward to take advantage of the breeze.

An elephant may also spray water on its ears, which also will cool down the blood before it returns to the rest of the body.

Large ears also trap more sound waves than smaller ones.

The ears of an African elephant are enormous. Each ear is about six feet from top to bottom and five feet across. A single ear may weigh as much as one hundred pounds.

When an elephant is angry or feels threatened, it may respond by spreading its ears wide and facing whatever it may perceive as a threat. The additional 10 foot ear span tacked on to an elephant’s wide body makes an already imposing animal look even bigger than it may usually appear.

Skin

African Elephant - Skin

Asian Elephant - Skin

The skin on an elephant can weigh as much as 2000 pounds, or over 900 kg.

Elephant skin lacks moisture so it must be loose, especially around the joints, to provide the necessary flexibility for motion.

The skin of the African elephant is more wrinkled than that of the Asian elephant. The wrinkles in an elephant’s skin help to retain moisture, keeping the skin in good condition.

The pink or light brown areas of skin on some Asian elephants are from a lack of pigmentation. This lack of pigmentation can be influenced by genetics, nutrition, habitat and age. The condition is not seen in African elephants.

The skin can be as thick as an inch on areas such as the back and as thin as 1/10 of an inch on the ears and around the mouth.

Despite it’s rough and dry appearance, the skin is delicate and may be soft to the touch.

The natural color is grayish black, but an elephant usually appears to be the same color as the soil where the elephant lives. This is because elephant’s take frequent mudbaths or dust with soil to protect against insects, to control body temperature, to condition and moisturize the skin, and to protect against sunburn.

One way a person regulates body temperature is by sweating – on a person, sweat glands are located throughout their skin. Elephants have very few sweat glands. The few sweat glands that an elephant has are located on the foot, near the cuticles. This results in a skin that is dry to the touch but soft and supple. If you look at an elephant on a hot day, you may see a wet area around the top of their toenails.

The only visible glands that are found on the skin of an elephant are the mammary glands and the temporal glands. Elephants have one temporal gland on each side of the head between the eye and the ear. The temporal gland is a large gland, much like a sweat gland, that sometimes produces a secretion that trickles down the side of the face. In female elephants, these glands may become active when the animal gets very excited. In male elephants, the temporal glands are active when the male is in “musth”, which is a condition very much like “rut” in a deer.

Teeth

Elephant Tusks

In addition to their tusks, which are modified incisors, an elephant will have four molars, with a molar located in each jaw. An African elephant will go through six sets of molars in a lifetime. Later in life, a single molar can be 10-12 inches long and weigh more than eight lb., or 3.6 kg.

An elephant’s molar is wide and flat, perfect for grinding. The surface of the molar differs between Asian and African elephants. The ridges on the chewing surface of an Asian elephant’s molar will run in parallel lines, while the ridges on the surface of an African elephant’s molar will form a diamond shape. This diamond shape led taxonomists to name the genus for African elephants, “Loxodonta”, which in Latin refers to this diamond shape.

There is no real tooth socket. As a molar is formed and utilized by the elephant, it passes through the jaw from back to front in a conveyor belt fashion. There are only four molars in use in an elephant’s mouth at any one time, but an elephant may go through six sets of molars in it’s lifetime. The final set typically erupts when the animal is in its early forties and must last for the rest of its life.

After these last sets of molars wear smooth, an elephant will have difficulty chewing and processing food, which in turn begins to contribute to a decline in the animals overall well-being. Ultimately the progression of teeth can dictate the length of an elephant’s life.

In addition to elephants, manatees and kangaroos also have teeth that move forward in the jaw in this fashion.

Thermoregulation

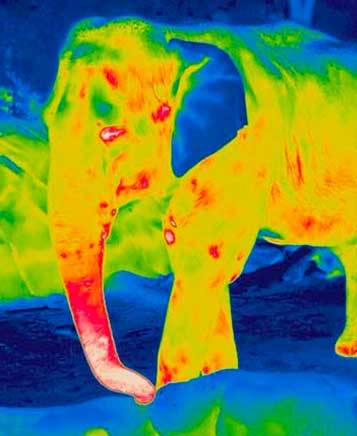

Elephants can fine tune their body temperature using “hot spots” scattered around their bodies, according to research which questions the widely held belief that the animals use their giant ears to stay cool.

With their thick hides and lack of sweat glands, it has long been thought that elephants rely upon their distinctive large ears and bathing in rivers to stay cool in hot climates. New research, however, has revealed that the world’s largest land animals have a secret trick to control their own body temperatures. Using thermal cameras, biologists have discovered that the creatures’ bodies are covered in “hot spots” that can help them lose heat.

By directing their blood supply near to the surface of small patches of skin scattered around their bodies, elephants can lose heat rapidly, allowing them to fine-tune their internal temperature. Scientists have long been puzzled by temperature regulation in elephants. Typically, animals with large bodies tend to retain more heat because, relative to their bulk, they have a small surface area for heat to escape from. Elephants, with their heavyweight frames, would appear to be at a disadvantage in the fierce heat of their African and Asian habitats, especially because they lack sweat glands – used for cooling by other mammals – and have tough hides to protect them from spiny bushes and trees.

It was assumed by biologists that the creatures, which weigh up to 13 tons (12 tonnes) when fully-grown, had evolved large ears to help them stay cool. The skin in the ears is thinner, so blood pumped into them cools down more readily.

But findings by researchers at two universities in Vienna have revealed that elephants also able to cool down by increasing the blood flow to skin patches in other parts of their bodies.

Nicole Weissenböck, an ecologist at the city’s University of Veterinary Medicine, who led the research, said: “Elephants are the largest terrestrial mammals on earth today. “They are called pachyderms (from the Greek language for “thick skin”) because of their supposed thick and insensitive skin. “Our study clearly shows that this is only a myth – in fact the elephant’s skin must have more regional concentrations of vascular networks that has previously been appreciated.

“It is a fine-tuning mechanism in heat regulation.” The researchers took thermal images of six African elephants at Vienna Zoo as they moved between outdoor and indoor environments to see how the temperature on their skin surface would change. Bright yellow and white colours indicated the parts of their bodies from which the animals were losing the most heat. The researchers found up to 15 “hot spots” scattered all over an elephant’s body surface, in addition to large patches on the ears. The study, which is published in the Journal of Thermal Biology, shows how these patches expand as the air temperature increases and more blood flows nearer to the skin surface. Subsequent experiments showed that elephants in the wild use the same “thermal windows” to control their body temperature.

Elephants have two additional ways to stay cool: ear-flapping, which creates a breeze, and bathing, which cools the creatures when the water evaporates from their skin. Together with these tricks, the skin hot spots allow the animals to keep their body temperature constant at about 36 degrees C – one degree less than humans. Professor Fritz Vollrath, an expert on elephant behaviour at Oxford University, said it was possible the hot spots provided localised cooling for specific organs. He said: “This is an interesting study as it shows that elephants can and do flood blood through their ears independently and can open and close specific areas of their skin for blood cooling.”

Source Article: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/wildlife/7663160/Elephants-use-hot-spots-to-stay-cool.html

Behavioral characterization of musth in Asian elephants

Musth is a heightened sexual state in male elephants that serves to announce breeding intent to females and to resolve male to male competition for access to females. It occurs regularly but asynchronously among males in a population and the onset of musth is triggered by a surge in serum androgens. These elevated androgens may cause male elephants to exhibit aggressive and or erratic behavior which can make musth males especially challenging to manage as musth functions to synchronize reproduction in in-situ elephant populations, recognizing the value of the sexual strategy may bolster breeding efforts to enhance the sustainability of ex-situ populations. Furthermore, elephant populations throughout the world managed by people within zoos and range countries such as elephant camps may require specialized care from well-experienced handlers as they can be dangerous to people and other elephants with whom they interact during musth. Similarly wild male elephants can be dangerous to surrounding human communities in range countries; male elephants are disproportionately implicated in incidence of human elephant conflict, a major threat to the well-being of local communities and the conservation of elephants alike.

Credit: Chase A. LaDue, Behavioral characterization of musth in Asian elephants (Elephas maximus): Defining progressive stages of male sexual behavior in in-situ and ex-situ populations