Abstract

Santalum album Linn. is an evergreen and hemi-parasitic tree, the heartwood-sandalwood of which was used during a long history in traditional Chinese medicine. Kuhnia rosmarinifolia Vent. is a good host for 1- or 2-year-old growing S. album. The interaction between S. album and K. rosmarinifolia is still little known. Many studies have been carried out on a number of plants for identification and diversity of endophytes. In this study, in total 25 taxa of endophytic fungi were isolated from the roots of S. album and the roots of K. rosmarinifolia. The most frequently isolated genera were Penicillium sp. 1 and Fusarium sp. 1 in the roots of S. album and K. rosmarinifolia, respectively. S. album is a root parasite of K. rosmarinifolia. The interesting result is that they apparently do not share the same endophytic fungi isolates. This study for the first time explored the content of endophytic fungi from S. album and K. rosmarinifolia, which provides important information for further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Endophytic fungi are defined as the endosymbionts that live within the plant intercellular and intracellular spaces for at least part of their life cycle without causing apparent harm to their host (Wilson, (1995)). Endophytic fungi have been reported to be associated with plants for over 400 million years (Krings et al., (2007)), and there are about one million species existing ubiquitously in plants (Shekhawat et al., (2010)). Endophytic fungi play important physiological (Malinowski et al., (2004)) and ecological (Malinowski and Belesky, (2006); Tintjer and Rudger, (2006)) roles in plant symbiosis, which protect their hosts from infectious agents and stressful environment by secreting bioactive secondary metabolites (Carroll and Carroll, (1978); Azevedo et al., (2000); Redman et al., (2002); Strobel, (2003); Rodriguez et al., (2004); Márquez et al., (2007)). Therefore, the study of endophytic fungus has become one of the popular topics in mycology.

Medicinal plants were used for many years in traditional Chinese medicine. Since the population is increasing, it is not possible to afford plant-based medicine because of the exhaustion of some of the plant resources. Medicinal plants are known for storing endophytic fungi, which are important sources of various secondary metabolites and bioactive compounds valuable for the pharmaceutical industry (Krishnamurthy et al., (2008); Khan et al., (2010)). Therefore, it is necessary to explore endophytic fungi in medicinal plants for developing some alternative medicines. Santalum album Linn. is an evergreen and hemi-parasitic tree belonging to the Santalaceae family, which is a well known plant distributed in India, Australia, New Zealand, South America, Indonesia, and other countries. It was introduced to China in the 1960s and widely cultivated in most tropical and subtropical areas in the 1980s. S. album, called “Tanxiang” in Chinese, was recorded in China Pharmacopoeia (State Pharmacopoeia Commission of China, (2010)) and its heartwood has been found to be particularly effective in activating “Qi” and warming the middle “Jiao”. It can also stimulate the appetite and eliminate pain. In addition, volatile oil extracted from S. album roots and heartwood has antiviral activity and antifungal activity (Viollon and Chaumont, (1994); Benencia and Courrèges, (1999); Sindhu et al., (2010)).

Xu et al. (2011) reported that Kuhnia rosmarinifolia Vent. from a seedling pot can be a good host for 1- or 2-year-old S. album. In the wild fields, we observed that 3- or 4-year-old S. album was near to K. rosmarinifolia, which grew up strongly. We also found that the leaf of S. album was yellow without any K. rosmarinifolia around, and S. album did not develop well. Previous studies investigated endogenous hormone levels and anatomical characters of haustoria in S. album seedlings before and after its attachment to K. rosmarinifolia (Zhang et al., (2012)). There is not enough information on endophytic fungi from S. album and its host plants. The endophytic fungi assemblages of parasite relationships have been reported in Cuscuta reflexa and its seven angiosperm hosts that showed no overlap between Cuscuta reflexa and Cucurbita maxima (Suryanarayanan et al., (2000)). While S. album is a hemi-parasitic plant, it can support nutrients by its own photosynthesis, but Cuscuta reflexa cannot.

The interactions between S. album and K. rosmarinifolia are interesting, but still little is known about how S. album and K. rosmarinifolia are connected with haustoria tissues, which would provide a conduit for diversion of the water and nutrients from the host to the parasite. However, the role of endophytic fungi in the root of the two plants is still unclear. In this study, we examined the hypothesis that the roots of S. album and its host K. rosmarinifolia are connected with each other by haustorium and consequently the same endophytes would be presented in both roots. We isolated and identified the endophytic fungi in the roots of S. album and K. rosmarinifolia for diversity determination and to explore the relationship between the endophytic fungi and S. album and K. rosmarinifolia in roots. To achieve spatial configuration of endophytic fungi, an anatomical study was undertaken on the two plant roots.

2

2.1 Source of plant samples

The healthy roots of S. album and its host of K. rosmarinifolia were collected from Guangdong Province (latitude 23°19′3.65″ N and longitude 115°59′27.99″ E), China. The plants were identified by Prof. Dr. Shun-xing GUO, Institute of Medicinal Plant Development, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, China. We studied three S. albums and three K. rosmarinifolias where each S. album was apart by 10–15 m. Five roots with haustoria issues of each S. album and K. rosmarinifolia were collected. The plant materials were brought to the laboratory in sterile polyethylene bags and stored temporarily in a refrigerator. The endophytic fungi were isolated within 24 h.

2.2 Isolation of endophytic fungi

To eliminate the epiphytic microorganisms, the roots were subjected to a surface-sterilized procedure. Each part of the samples was thoroughly washed under running tap water. Then the samples were sterilized by submerging the part in 75% ethanol for 1 min, followed by immersion in 3% NaClO for 8 min, then repeated in 75% ethanol for 30 s and rinsed three times in sterile distilled water, and the pieces were blot-dried on sterile blotting paper. The roots were cut into 5 mm-length segments. About 4–5 segments were placed into a petri dish (diameter 90 mm) with potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium containing 50 mg/L oxytetracycline and 50 mg/L penicillin (Otero et al., (2002)). Samples were incubated at 25 °C in dark conditions (Cui et al., (2010)). The fungi were observed every 2 d for at least 3 weeks.

The fungi that grew from the segments were periodically isolated and identified using morphological characteristics by transferring the hyphal tips to the fresh PDA plates without antibiotics. The pure endophytic fungal strains were photographed and preserved in the Laboratory of Mycology, Biotechnology Center, Institute of Medicinal Plant Development, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

The colonization frequency (CF) of an endophyte species in the root tissue was calculated by CF=(N col/N t)×100%, where N col is the number of segments colonized by each endophyte and N t is the total number of segments studied (Hata and Futai, (1995)).

The contribution to an endophyte assemblage by the dominant endophyte (DE) was calculated as the CF of the DE divided by the sum of CF of all the endophytes in an assemblage (×100%). To compare the endophyte assemblage of the host and its hemi-parasite combination, a similarity coefficient was calculated as (Carroll and Carroll, (1978)) Similarity coefficient=[2w/(a+b)]×100%, where a is the sum of CF for all fungal species on the host, b is the similar sum for its hemi-parasite, and w is the sum of lower colonization frequencies for fungal species in common between the host and the hemi-parasite.

2.3 Measurements and analysis

The fresh and clean samples of two plants were obtained from the representative roots with blades and cut into segments (0.5–1.0 cm in length). The root segments were fixed in formalin, dehydrated alchohol, and glacial acetic acid (FAA) fixative for at least 72 h, dehydrated in ethanol at gradient concentrations from low to high, embedded using paraffin, sliced by paraffin sections with a thickness of 10 µm, dyed in safranin-fast green, and then observed under a microscope (ZEISS, AxioImager AI, Germany).

2.4 DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification

Endophytic fungi failing to sporulate were identified using molecular biological analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of rDNA. Molecular methods are useful for evaluating microbial communities’ structures and functions. DNA analyses have been applied in different fields for whole communities, bacterial, fungal, and so on. Therefore, a high quality and quantity of DNA is essential. After cultivation for 1 or 3 weeks at 25 °C in the dark, all pure strains were selected for DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing. Primers ITS1 and ITS4 constructed for molecular phylogenetic studies (White et al., (1990)) were used to amplify the ribosomal ITS. The partial nucleotide base-pair fragment of the ITS ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene from the isolated endophytic fungus was amplified using PCR with universal ITS primers ITS1 and ITS4. PCR was carried out as follows: the reaction mixture in a total volume of 25 μl containing 12.5 μl Mix (10× buffer (with Mg2+) and 10 μmol/L dNTPs), 9.5 μl double distilled water, 1 μl (10 μmol/L) each primer, and 1 μl genomic DNA.

The PCR was done in a thermal cycler with the following conditions: 3 min initial denaturation at 94 °C, 32 cycles of 30 s denaturation 94 °C, 25 s annealing at 55 °C and 30 s elongation at 72 °C, and 7 min final elongation at 72 °C. Single-band PCR products were purified using Watson’s PCR purification kit (Watson, China). Sequencing was performed with Big Dye Terminator sequencing kit and an ABI 3730 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA). All the sequences obtained in this study were submitted to GenBank and the accession numbers of the sequences are JX657338-JX657350 and JX573315-JX573326.

2.5 Sequence analysis

BLAST searches (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ BLAST) (Altschul et al., (1997)), using ITS1-5.8S rDNA-ITS2 as query sequences, were conducted on all the sequences to check their closest known relatives. The isolates were arranged as the closest to a certain genus and, when identified in a database, the matches were about 95%. However when the similarity was less than 95%, the strain was considered unidentified (Sánchez Márquez et al., (2008)).

3 Results and discussion

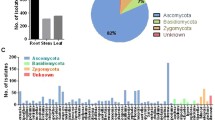

A total of 68 fungal isolates were obtained from 160 segments (roots) of the two plants, of which 34 from 80 root segments of S. album were classified into 13 species, and 24 from 80 root segments of K. rosmarinifolia were grouped into 12 species. The dominant endophytic fungi in each host plant were quite different. Penicillium sp. 1 was the dominant fungal species in the roots of S. album and Fusarium sp. 1 was the dominant species in the roots of K. rosmarinifolia (Table 1).

The CF was used for diversity analysis. In our study, all the cultured strains were selected for sequence by the ITS region of nuclear rDNA. Twenty-five fungal species in the roots of S. album and K. rosmarinifolia were isolated, and 24 species belonged to Ascomycota. One fungal species failing to sporulate was designated as sterile fungus, 22 endophytic fungal species of Ascomycota were classified into four classes: Sordariomycetes (11), Eurotiomycetes (6), Dothideomycetes (4), and Leotiomycetes (1). Four endophytic fungal species belonged to the genus of Penicillium, five endophytic fungal species belonged to the genus of Fusarium. Only one species belonged to the group of sterile fungi and thus cannot be identified on the basis of morphology and its sequence reveals 89% identity with Lophiostoma cynaroidis in BLAST (Table 2).

A total of 13 fungal species isolates were isolated from the root of S. album plants, while K. rosmarinifolia plants had 12 fungi species as endophytes. The overall CF was determined as 42.5% on the surface sterilized tissues from S. album plants, while overall CF was determined as 30% on the surface sterilized tissues from K. rosmarinifolia plants (Table 1). The most frequently isolated genus was Penicillium sp. 1 in the roots of S. album and Fusarium sp. 1 in the roots of K. rosmarinifolia (Table 2).

The roots of S. album and K. rosmarinifolia are connected with haustorium (Fig. 1). Fungal colonization was observed both intercellularly and intracellularly and was only involved in the cortical cells of the roots of S. album and K. rosmarinifolia. In this region, a widespread occupation by intercellular and intracellular hyphae was observed (Fig. 2). The hyphae in the cortex frequently grew into adjacent cortical cells rather than into the cylinder of vascular tissues of two plant roots and occasionally a peloton were observed. We had expected a high similarity in the endophytic fungi in the two roots, but the results were the reverse. We proposed that sandalwood oil in the roots of S. album may be a defense against the endophytic fungi in the roots of K. rosmarinifolia because of haustoria tissues. In our work, we got the result that there are no similar endophytes when comparing S. album with K. rosmarinifolia (Table 2). A similar study reported by Suryanarayanan et al. (2000) showed that the endophyte assemblages of Cucurbita maxima and its Cuscuta reflexa parasite overlapped by 0%. These results strongly suggest the existence of some degree of host specificity among endophytic fungi. Zhang et al. (2012) firstly reported a relationship between endogenous hormone profiles and structural characters of haustoria before and after attachment to the host K. rosmarinifolia in S. album. The study also found that many lysosomes occurred in the cells of haustorium. Lysosome contains digestive enzymes which are used to digest invasive microorganisms and break down unwanted or damaged cell organelles, which inhibited endophytes from growing and surviving in haustorium. PDA is the most common medium used for separation of cultivable endophytic fungi. In addition, all endophytic fungi were not separated in the present study because we were only concerned with the cultivable endophytic fungi, which may show a bias in the results. In short, the hormones might act as a web-like set of interactions to regulate the haustorial development of S. album and water and nutrient transport in the parasite-host association. However, the endophytic fungi might not act like this.

Distribution of endophytic fungi in the roots of Kuhnia rosmarinifolia (a) and Santalum album (b)

Examples of transverse sections of K. rosmarinifolia (a) and S. album (b) roots. Cortex of the roots of K. rosmarinifolia (a) and S. album (b), showing the infected place (*) and the infected cell in cortex. Arrow represents the hyphal coils formed by hyphae infected into the cortex cell from one to another, and peloton formed by the fungi colonization in cortex cells. Co: cortex; H: hyphae; P: peloton

4 Conclusions

This paper explores the haustorium development and the mechanism of parasitism in the sandalwood tree. We reported for the first time that there were different endophytes between S. album and K. rosmarinifolia in roots. Moreover, endophytic fungi were isolated firstly from S. album and K. rosmarinifolia. Endophytic fungi in the roots of S. album and K. rosmarinifolia are not the same and are only involved the cortical cells of the roots of S. album and K. rosmarinifolia, which provides new information for further studies.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Si-sheng SUN, Xiao-mei CHEN, and Shun-xing GUO declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schäffer, A.A., et al., 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25(17):3389–3402. [doi:10.1093/nar/25.17.3389]

Azevedo, J.L., Maccheroni, W.Jr., Pereira, J.O., et al., 2000. Endophytic microorganisms: a review on insect control and recent advances on tropical plants. Electron. J. Biotechnol., 3(1):40–65. [doi:10.2225/vol3-issue1-fulltext-4]

Benencia, F., Courrèges, M.C., 1999. Antiviral activity of sandalwood oil against Herpes simplex viruses-1 and -2. Phytomedicine, 6(2):119–123. [doi:10.1016/S0944-7113 (99)80046-4]

Carroll, G.C., Carroll, F.E., 1978. Studies on the incidence of coniferous needle endophytes in the Pacific Northwest. Can. J. Bot., 56(24):3034–3043. [doi:10.1139/b78-367]

Cui, J.L., Guo, S.X., Xiao, P.G., 2010. Antitumor and antimicrobial activities of endophytic fungi from medicinal parts of Aquilaria sinensis. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B (Biomed. & Biotechnol.), 12(5):385–392. [doi:10.1631/ jzus.B1000330]

Hata, K., Futai, K., 1995. Endophytic fungi associated with healthy pine needles and needles infested by the pine needle gall midge, Thecodiplosis japonensis. Can. J. Bot., 73(3):384–390. [doi:10.1139/b95-040]

Khan, R., Shahzad, S., Choudhary, M.I., et al., 2010. Communities of endophytic fungi in medicinal plant Withania somnifera. Pak. J. Bot., 42(2):1281–1287.

Krings, M., Taylor, T.N., Hass, H., et al., 2007. Fungal endophytes in a 400-million-yr-old land plant: infection pathways, spatial distribution, and host responses. New Phytol., 174(3):648–657. [doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007. 02008.x]

Krishnamurthy, Y.L., Naik, S.B., Jayaram, S., 2008. Fungal communities in herbaceous medicinal plants from the Malnad region, Southern India. Microbes Environ., 23(1): 24–28. [doi:10.1264/jsme2.23.24]

Malinowski, D.P., Belesky, D.P., 2006. Ecological importance of Neotyphodium spp. grass endophytes in agroecosystems. Grassland Sci., 52(1):1–14. [doi:10.1111/j.1744- 697X.2006.00041.x]

Malinowski, D.P., Zuo, H., Belesky, D.P., et al., 2004. Evidence for copper binding by extracellular root exudates of tall fescue but not perennial ryegrass infected with Neotyphodium spp. endophytes. Plant Soil, 267(1):1–12. [doi:10.1007/s11104-005-2575-y]

Márquez, L.M., Redman, R.S., Rodriguez, R.J., et al., 2007. A virus in a fungus in a plant: three-way symbiosis required for thermal tolerance. Science, 315(5811):513–515. [doi:10.1126/science.1136237]

Otero, J.T., Ackerman, J.D., Bayman, P., 2002. Diversity and host specificity of endophytic Rhizoctonia-like fungi from tropical orchids. Am. J. Bot., 89(11):1852–1858. [doi:10. 3732/ajb.89.11.1852]

Redman, R.S., Sheehan, K.B., Stout, R.G., et al., 2002. Thermotolerance generated by plant/fungal symbiosis. Science, 298(5598):1581. [doi:10.1126/science.1078055]

Rodriguez, R.J., Redman, R.S., Henson, J.M., 2004. The role of fungal symbioses in the adaptation of plants to high stress environments. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Gl., 9(3): 261–272. [doi:10.1023/B:MITI.0000029922.31110.97]

Sánchez Márquez, S., Bills, G.F., Zabalgogeazcoa, I., 2008. Diversity and structure of the fungal endophytic assemblages from two sympatric coastal grasses. Fungal Divers., 33:87–100.

Shekhawat, K.K., Rao, D.V., Batra, A., 2010. Morphological study of endophytic fungi inhabiting leaves of Melia azedarach L. Intl. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 5(3):177–180.

Sindhu, R.K., Upma, K.A., Arora, S., 2010. Santalum album Linn: a review on morphology, phytochemistry and pharmacological aspects. Intl. J. PharmTech. Res., 2(1): 914–919.

State Pharmacopoeia Commission of China, 2010. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. China Medical Science Press, Beijing, China, p.357–358 (in Chinese).

Strobel, G.A., 2003. Endophytes as source of bioactive products. Microbes Infect., 5(6):535–544. [doi:10.1016/ S1286-4579(03)00073-X]

Suryanarayanan, T.S., Senthilarasu, G., Muruganandam, V., 2000. Endophytic fungi from Cuscuta reflexa and its host plants. Fungal Divers., 4:117–123.

Tintjer, T., Rudger, A.J., 2006. Grass-herbivore interaction altered by strains of a native endophyte. New Phytol., 170(3):513–521. [doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01720.x]

Viollon, C., Chaumont, J.P., 1994. Antifungal properties of essential oils and their main components upon Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycopathologia, 128(3):151–153. [doi:10.1007/BF01138476]

White, T.J., Bruns, T.D., Lee, S., et al., 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., et al. (Eds.), PCR Protocols: a Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press, San Diego, California, p.315–322.

Wilson, D., 1995. Endophytes: the evolution of a term, and clarification of its use and definition. Oikos, 73(2): 274–276.

Xu, D.P., Lu, J.K., Liu, X.J., et al., 2011. Mixed plantation of Santalum album and Dalbergia odorifera in China. Asia and the Pacific Workshop on Multinational and Transboundary Conservation of Valuable and Endangered Forest Tree Species, Guangzhou, China, p.17–18.

Zhang, X.H., Teixeira da Silvab, J.A., Duan, J., et al., 2012. Endogenous hormone levels and anatomical characters of haustoria in Santalum album L. seedlings before and after attachment to the host. J. Plant Physiol., 169(9):859–866. [doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2012.02.010]

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Project supported by the National Mega-Project for Innovative Drugs (No. 2012ZX09301002-001-032) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31170016)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Ss., Chen, Xm. & Guo, Sx. Analysis of endophytic fungi in roots of Santalum album Linn. and its host plant Kuhnia rosmarinifolia Vent.. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 15, 109–115 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1300011

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1300011