- Detroit’s Lexus Velodrome opened in January 2018 and got 35,000 visitors in its first year.

- Built by legendary velodrome designer Dale Hughes, the Lexus aims to grow a major track cycling scene in Michigan.

- Hughes wants to develop local talent and launch an American track cycling league from the facility.

Jimmy Capela won $115 last month racing at the velodrome. But back at Renaissance High School in Detroit, not all of the 14-year-old freshman’s friends even know he’s a track cyclist.

“Some have no clue, but about half know that I do it, and they think that it’s pretty cool. But they haven’t really tried it out for themselves,” Capela said. “Others think it’s weird, because nobody does that anymore.”

Even fewer kids his age understand Capela’s dedication: six days a week at the Lexus Velodrome, racing, training, constantly improving. While his peers obsess over basketball and football, he said, he dreams of joining a cycling team in college, turning pro, and winning Olympic gold.

Capela and his older brother, Jackson, began riding five years ago at Bloomer Park, another velodrome in Rochester Hills, Michigan, a far northern suburb of Detroit. They switched to the Lexus Velodrome when it opened in January 2018. After all, it’s much closer to home—right here in their city.

The Detroit Fitness Foundation, a non-profit that runs the 64,000-square-foot Lexus Velodrome, reported strong first-year numbers for the facility: $900,000 in revenue (leaving it only $50,000 in the red) and an estimated 35,000 people through its doors. In year two, ambitions include raising revenues to $1.5 million and launching an American professional track cycling league.

“With the indoor velodrome and its location in the city, it’s really grown the opportunity to get people into the sport. Without it, they might have never been able to participate in cycling,” said Chris Donnelly, president of the Michigan Bike Racing Association. “The first year has been about growing and establishing themselves, but they’re really getting up to speed now.”

The mastermind behind the Lexus is a legend in the tiny world of velodrome design. Dale Hughes has built about 25 tracks around the world, including Bloomer Park; venues for the Asian, Commonwealth, and Pan American games; and, most famously, the track for the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

Hughes, 69, has never left his metro Detroit home. A longtime presence in Michigan cycling, he was an ideal candidate to spearhead the dream of a Detroit track from the anonymous donor—a mysterious cycling lover with a small fortune from the auto industry—who bankrolled the facility’s $4.5 million in start-up costs.

With ample funding and freedom, Hughes crafted his dream facility. The Lexus has three “fields of play”: the 166-meter track itself (one of three indoor tracks in the U.S.), a 1,200-square-foot fitness studio, and a flat running track around the outside. All three operate simultaneously, and the facility has hosted activities as varied as disc golf, roller derby, bike polo, a car show, and a Kentucky Derby party where cyclists raced as the horses.

The infield is available for events, and during races it’s filled with a lounge selling booze and food, plus party suites with couches inches from the track—and TVs to watch the riders zoom around the other side.

“It’s a very cool atmosphere, and there’s an energy to the place. There’s a lot of stuff going on,” Donnelly said. “It’s been really positive that way, as a central hub for the cycling community.”

Hughes believes the future of track cycling lies in exciting, spectator-centric races, and all the velodrome’s amenities are geared toward that vision: the bar, the suites, the $10 ticket prices, the constant races in various formats, the generous prize money, and even the relatively small track size.

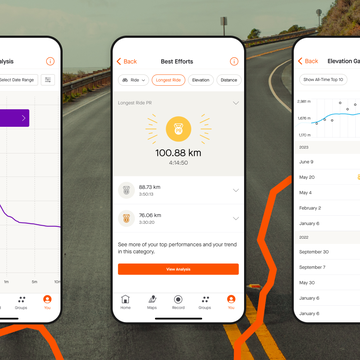

Everything is livestreamed and blasted out on social media, and Detroit’s local PBS station broadcasts select races. Hughes said he plans to use these events as the foundation for his proposed track cycling league—he’s calling it the American Cycling League—beginning with a 10-race series in September.

“With this, it’s like a video game,” said Frankie Andreu, the former U.S. Postal Service team captain, about riding the tight curves of the Lexus track. “Watching is super exciting. Racing it is exciting.”

Andreu, 52, was born in Dearborn, a city bordering Detroit to the southwest, and grew up riding the long-gone Dorais Velodrome. He competed as a track cyclist in the 1988 Seoul Olympics before turning pro the following year.

“In the Dorais days, there was a very active racing scene, and I see a lot of similarities [to the Lexus],” Andreu said. “When I go to ride, I see these young kids, they’re doing well. I think it can definitely develop some national champions. Where it goes from there, I don’t know.”

Hughes is clearly focused on local development. Posters of Eddie Tolan and Major Taylor—both legendary black American athletes, with Tolan being a Detroiter—hang on the Lexus’s walls. Its staff of around a dozen has mounted a steady outreach campaign to local schools, explaining what the velodrome offers and inviting students to tour the facility and learn about cycling history.

Capela’s mother, Myrna Capela, works on her own time to regularly bring dozens of students to the Lexus. (“It makes me want to cry when I think about the impact it’s had,” Capela told Crain’s Detroit Business in February.) Nearby Ben Carson High School and Spain Elementary-Middle School use the facility as a gym space.

“Around 75 percent of the riders on my track now had never ridden on a track six months ago,” Hughes said. “Fifty percent had never seen a velodrome in their life, and I think that’s the sad case around the country. Our goal is to get people in the door, and then hopefully we can hook a few of them into wanting to participate. I’m winning one rider and one spectator at a time.”

To encourage Detroiters to get involved, the Lexus offers free programming, free bikes and equipment, and free summer camps. Hughes figured that 300 people might participate this June, and some will stick around for good.

In July, eight riders from the Lexus’s growing youth cohort traveled to Trexlertown, Pennsylvania, for the junior track nationals, with the velodrome paying most of the expenses. They came away with four medals and several more top-10 finishes. Hughes hopes to take twice the number of riders to the nationals in California this summer.

“All we’re looking for is one kid that can be the next Olympic gold medalist,” said Travis Smith, who runs the Velo Sports Center, the venue hosting the junior track nationals this year and home of Team USA Track Cycling. “Who knows how you’re going to find them. You just need one.”

Jacob joined Runner’s World and Bicycling as an editorial fellow after graduating from Northwestern University in 2018, where he studied journalism. His work focuses mainly on news and service pieces for both audiences, with the occasional foray into longer feature work and product reviews. He especially loves to highlight the journeys of unique runners and riders doing amazing things in their communities.