Combating flatworms: A look at ways to fight back–and perhaps the ultimate weapon

Article & images by Daniel Knop

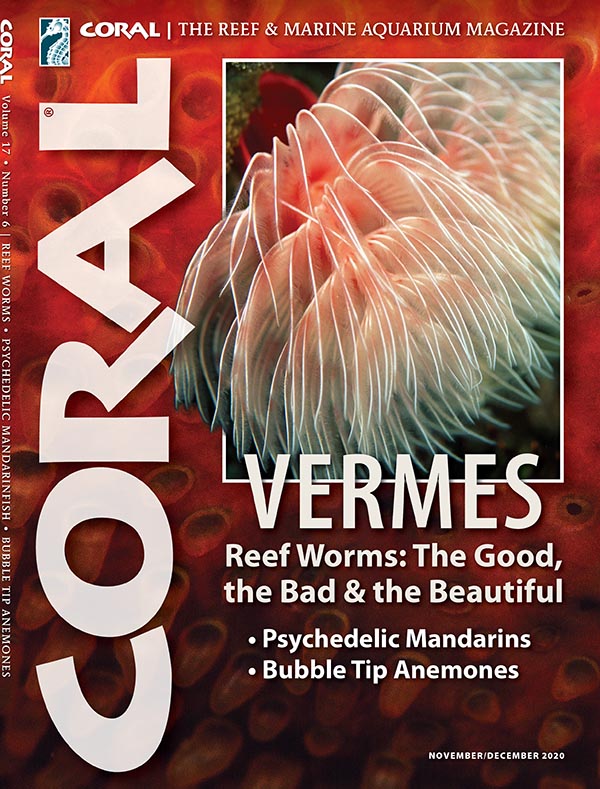

Excerpt from CORAL Magazine, November/December 2020

Exasperated aquarists and problems with flatworms in the reef aquarium have a long history, as do attempts to combat them. In the 1980s, malachite green oxalate was regarded as the method of choice. It was a familiar medication in the aquarium hobby, as it was used to treat fishes in quarantine tanks against fungi and parasites, especially Ichthyophthirius. Some aquarists tried to get rid of the flatworms that proliferated in their reef tanks with few fishes—and then in the reef aquarium itself.

The good news was that it worked: the flatworms died. The bad news was that lots of the corals died, too. I remember large populations of Anthelia falling victim to my own attempt, in 1988, to free them from the masses of Waminoa flatworms in my tank. Even an Octopus vulgaris failed to survive my attempt to kill Convolutriloba flatworms with this medication. Many aquarists reported success back then, but the variety of species of invertebrates that were maintained in reef tanks in those days was limited, and so there were often very few, if any, creatures in the tank that were sensitive to it.

Various other drug solutions, some borrowed from veterinary medicine, have come and gone in the marine aquarium trade, but many have caused the deaths of corals and other delicate organisms, and few experienced reefkeepers today are comfortable introducing any form of chemical pesticide into their systems.

Biological controls

People wondered about biological countermeasures and searched for fishes that ate flatworms. Occasionally a Synchiropus sp. dragonet, a small Sixline (Pseudocheilinus hexataenia), a Golden Wrasse (Halochoeres chrysus), or another fish could be observed picking at a flatworm. This observation was rapidly converted into advice on biological control, but it hardly ever solved the problem. A species-rich population of fishes can perhaps act as a prophylactic measure to prevent the proliferation of Convolutriloba flatworms; observations suggest that such plagues develop more often in fish-free tanks or those with a very sparse fish population. But stopping a mass proliferation is practically impossible, and observations to date suggest that the density of the fish population has no effect on Waminoa flatworms.

When the word went around that a natural predator of flatworms had been found, the aquarist community was overjoyed. The Blue Velvet Headshield Sea Slug, Chelidonura varians, an opistobranch gastropod, is a beautiful little creature that deliberately goes in search of flatworms, creeps up on them, and sucks them in like a vacuum cleaner, one after another. That was the good news. The bad news was that, after about two weeks, these gastropods became sluggish, sat motionless in strong current, and hardly fed at all. If you touched them briefly, they would creep around again for a while, perhaps eating two or three flatworms, but then they would sit motionless again until they died. What happened? We can only speculate about this, but it may be that the flatworms protect themselves with toxins that can sicken or kill predatory enemies. The bottom line is that head-shield slugs are not a good solution, as they will not survive in most aquariums, and they should be left on the wild reef.

Fortunately, there are now options both for treatment in the aquarium and for external immersion-bath treatment, both of which appear to solve the flatworm problem.

External bath treatment

In the event that a coral colony, either a new acquisition or an established specimen in the reef aquarium, is infested with Waminoa or Convolutriloba, you may want to resort to a chemical treatment—not the malachite green oxalate of the 1980s or the levamisole hydrochloride of the 1990s, but a therapeutic dip.

A number of products are now available for ridding corals of a variety of pests, including acoel flatworms and “red bugs.” These are usually applied by giving the coral a quick bath that kills or stuns the undesirable parasites but does not harm the coral. Among the currently popular and reportedly effective dips are (alphabetically): Coral Rx by Blue Ocean, Flatworm eXit by Salifert, Koral MD Pro by Brightwell, Reef Dip by SeaChem, Revive Coral Cleaner by Two Little Fishies, and The Dip by Fauna Marin. In using any such product, the aquarist is strongly urged to follow the maker’s instructions to avoid having the treatment stress or kill the patient.

Other treatments are available, including one that has undergone some scientific testing with published results. This procedure to kill acoels derives from Yan Li, who is studying Acropora-eating flatworms, and who uses the active ingredient beta-cyfluthrin. This is a manufactured version of a botanical pyrethroid, which is contained in many plant pesticides. It kills the Acropora-eating flatworms but doesn’t have any noticeable effect on the health of the corals. Yan Li recommends the following procedure for elimination: He uses one drop of a 4.5-percent beta-cyfluthrin oil emulsion in one liter of seawater, homogenizes the mixture, and immerses the infected coral for ten minutes. It should be moved vigorously during treatment (or flushed with the current from a small powerhead), as these flatworms easily detach from the host and swim away. He next rinses the coral several times in clean sea water, then drips the gel-like beta-cyfluthrin oil emulsion directly onto any visible flatworm eggs and allows it to take effect. He says treatment should be repeated several times at seven-day intervals. (See References.)

Following any dip, the coral should be rinsed in clean water from the reef system and, ideally, put into quarantine for observation. Quarantine was once used only for newly acquired fishes, but many reefkeepers are now aware that incoming corals can bring problems and pests, including flatworms. A week or two in a small aquarium where the owner can closely view the coral and watch for any hitchhikers is both an interesting exercise and a protocol that safeguards a valuable collection of corals in the display reef.

In-tank eradication:

The Lanthanum treatment

When faced with a horrendous mass proliferation of flatworms in the aquarium, biological controls and spot treatment of individual corals may not be adequate. Fortunately, there is a solution, and it is both unexpected and quite different: Lanthanum!

In CORAL back in 2009, I discussed phosphate reduction using lanthanum chloride (LaCl3) after I encountered it in the U.S. swimming pool industry (the substance is used there to prevent algae growth in swimming pools that results from high phosphate concentrations). Plus, Joe Yaiullo, director of the Long Island Aquarium (formerly Atlantis Marine World), was using lanthanum to lower the phosphate concentration in his stony-coral-filled 20,000-gallon (76,000-L) reef aquarium.

Later, a phosphate-reducing agent containing lanthanum arrived on the market in Germany under the name Elimi-Phos Rapid. It was sold by Tropic Marin, a company that produces and sells it to remove phosphate. They make no claims about the product having any biocide capability, but in many cases aquarists who used it found that a side effect of lanthanum treatment was quick eradication of flatworms of the genera Waminoa and Convolutriloba.

Flatworms of both genera disappear completely at the dosage of 1.0 ml/100 L of aquarium water recommended by the manufacturer. On the basis of observations to date, damage to fishes or corals is unlikely, provided the treatment is carried out as prescribed. You can also repeat this treatment regularly to lower phosphate concentration.

What could be happening? Why are flatworms being killed while corals, fishes, and other animals are unharmed?

Dr. Samuel Nietzer, coral biology researcher at the University of Oldenburg and frequent CORAL contributor, says that the toxic effect of lanthanum on flatworms has been known and utilized for a while. “I have personally used Elimi-Phos Rapid to kill off the orange Convolutriloba retrogemma (red ‘planaria’ or rust flatworms), which worked great,” says Nietzer. “You just have to make sure to either use loads of activated carbon afterwards and/or do a water change, because the dying flatworms can release toxic compounds. And, of course, be sure you don’t lower the PO4 concentration too much or too rapidly. I don’t have experience with AEFW, though. But I assume it should work, too. There are also scientific publications on the mechanisms of how lanthanum chloride is killing the flatworms,” Nietzer continues. “It seems to be messing with their ion channels.”

A study reported by Wayne Briner at Ashford University (San

Diego) in 2018 looks at the possible underlying mechanisms. After testing the effects of LaCl3 on common freshwater planaria flatworms

(Girardia dorotocephala), Dr. Briner concluded: “Typically thought of as a Ca channel blocker, particularly at the L-type channel, La has direct or Ca-mediated effects on Cl, K, Mg, and Na channels and metabolism. The mechanisms of La activity, especially at toxic concentrations, are quite diverse and complex and will require considerably more study before being completely elucidated.” The mechanism for how lanthanum works and how other compounds present in the flatworms’ environment can affect its action is not fully understood at this time.

A protocol for using lanthanum is shown in the accompanying sidebar (CORAL Magazine, November/December 2020, page 62). It is important to follow the directions from the companies that provide phosphate-removing lanthanum in the aquarium. Cheap, industrial-grade lanthanum chloride sold for use in swimming pools should be avoided, as it can be easily overdosed and has reportedly resulted in the death of reef animals.

Based on my own experiences with lanthanum over more than a decade, I believe that you should never pour the lanthanum solution directly into the aquarium. That is how it is used in the swimming pool, but in the reef aquarium the resulting white flocculant precipitates will settle out all over the tank. As detailed in my CORAL article (see references), I discussed my simple method of lanthanum filtering, in which the water is mechanically filtered over nylon wool immediately after the drop-by-drop addition of the treatment. The surest way to dose a system with lanthanum is to add it to the sump or filter chamber before the water flows through a mechanical filter and/or protein skimmer.

You should, in addition, always make sure that the phosphate concentration in the water doesn’t drop too low during any lanthanum treatment to kill flatworms. During treatment, always filter through activated carbon to trap any toxins that are flushed out of the flatworm bodies. This has proved to be particularly important in the case of dense Convolutriloba populations, where it may also be advisable to siphon off as many of the worms as possible beforehand so that they don’t die in the aquarium system.

AEFW (Prosthiostomum acroporae) plagues are now just as controllable as those of Convolutriloba or Waminoa species. The new, scientifically undescribed Acropora-eater that Yan Li (2019) calls NAEFW also falls into this category. If your corals have problems with these worms, you have two options: treatment of the entire aquarium or external immersion treatment of infested corals.

If you want to free the entire aquarium from Prosthiostomum acroporae or NAEFW, then use lanthanum as described here for the genera Waminoa and Convolutriloba. It is advisable to repeat the treatment several times, always with thorough mechanical filtration of the water immediately after the lanthanum is added.

References

Briner, Wayne. (2018). The Toxic Effect of Lanthanum on Planaria Is Mediated by a Variety of Ion Channels. Toxics 6, no. 2: 33. doi: 10.3390/toxics6020033.

Brockmann, Dieter. (2017). Phosphatentfernung durch Lanthan—ein Erfahrungsbericht. KORALLE 105, 18 (3): 64–69.

Knop, Daniel. (2009). Foiling Phosphate: A Look at Lanthanum Chloride Use in the Aquarium. www.coralmagazine.com/lanthanum2009

Knop, Daniel. (2009). Phosphat ade, oder: Lanthan in der Korallenriffaquaristik. KORALLE 57, 10 (3): 58–65.

Li, Y. (2019). Ein neuer Plattwurm, der Acropora frisst. Lynford, Andrew H. (2009). Evaluation of Chemical Eradication Methods of Acoels (Acoelomorpha) From Marine Aquaria. Advanced Aquarist, 2009/4.