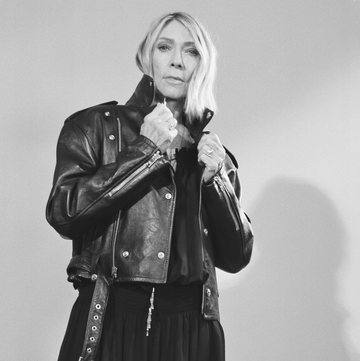

Just a few days before Roxana Saberi was to be released from Tehran's infamous Evin prison in the spring of last year, her cell mates treated her to an eyebrow threading. Having spent more than a month behind bars accused of spying for the U.S. government, the Iranian-American journalist was optimistic that — this time — her captors would keep their word and free her. "I thought, Well, if I'm going to see [my boyfriend], I don't want a monobrow," recalls Saberi, 32, who chronicles her ordeal in the new book Between Two Worlds.

A week later, Saberi was still in prison. Her release was once again postponed; whether she would languish in Evin, Iran's jail of choice for political prisoners, for another week — or for years — was impossible to predict.

So how did Saberi, once a top-10 Miss America finalist, wind up in jail in Iran?

If the Islamic republic seems an odd choice for a beauty queen from unassuming North Dakota, Saberi was never the stereotypical pageant girl. The daughter of a Japanese mother and an Iranian father, she entered her first competition, Miss Fargo, on a whim. "The organizer said, 'We only have three girls and we need at least four, so will you compete?' I can barely walk in heels," laughs Saberi, speaking by phone from her parents' Fargo home. Nevertheless, she won and ended up nabbing 1997's Miss North Dakota crown, winning scholarships to fund master's degrees from Northwestern and Cambridge. Planning to jump-start her career as a foreign correspondent, Saberi, then 25, used family connections to move to her father's homeland, a country hardly known for welcoming foreign journalists.

Upon arriving in Iran, Saberi, who had once strutted confidently in an evening gown on national TV, covered her head with a traditional hijab and settled into life in Tehran. For six years, everything went according to plan. She filed reports for the BBC, Fox News, and NPR and spent her spare time working on a book on contemporary Iranian society. Then, on the morning of January 31, 2009, her doorbell rang. She answered and was greeted by four Iranian intelligence agents. The men searched her apartment, seizing her notepads, cell phone, books, family photos, and, most frighteningly, her passports. "I felt violated, outraged, shocked, and, most of all, scared that four plainclothesmen were alone with me in my apartment, sifting through my belongings," remembers Saberi. Not satisfied with her truthful answers about her work, one of the agents insisted, "You were using your book as a cover? to gather intelligence for the CIA."

Saberi was blindfolded and escorted to Evin. She was strip-searched, issued beige prison garb, and tossed alone into a seven-by-nine-foot cell. "I was so scared because nobody knew where I was. I had heard about what happened in that prison," she says with a shudder, referring to reports of torture, hangings, and mass executions.

At Evin, Saberi was at the mercy of a Kafkaesque legal system, not knowing what the charges were against her or when she'd be released and delayed access to a lawyer. "It wasn't just home, it was freedom that I missed," she says now. "I realized the value of very simple things — to make a phone call or go to the bathroom when you want — things that I had taken for granted."

While Saberi was never physically harmed, her captors used psychological tactics against her in seemingly endless interrogations. They threatened her with a life sentence or worse and implied that even if she were released, she would meet a grisly fate. "They told me, 'We have agents all over the world. If you're [reporting] in Afghanistan, you might get killed in a car accident.' I knew they were capable of such things." Yet they regularly dangled the prospect of freedom before her. If only she would admit her so-called crimes, they would let her go. Lying awake one night in her cell, she writes in her book, she decided, "I have no choice left but to lie for my life."

Finally, on February 2, 2009, the third day of interrogations in which questions ranged from the mundane (What did her parents do?) to the delusional (What type of reports did she do, and how did this help the CIA?), Saberi broke down. "Some prisoners call it white torture. It doesn't leave a mark on your body, but it does on your mind," she says. "They don't have to lay a finger on you." She filled a notebook with phony admissions, stating she used her book as a pretext for espionage. "That was my low point."

Riddled with guilt, just more than a month later, she recanted her confession before a magistrate, writing, "I would rather tell the truth and risk staying in prison than win my release by telling lies.... I am not a spy." It was a bold move — and one that cost her dearly. Her release, which seemed imminent, was denied. Instead, following a one-day trial, she was condemned to eight years in jail.

By now, Saberi's fear had taken a backseat to defiance. What did she have left to lose? "I hadn't predicted I would get such a steep sentence, but I felt proud for having stood up to them." Two days after her April 18 sentencing, she went on a hunger strike, determined to bring media attention to her situation. After two weeks of surviving on water and honey, she weighed a mere 99 pounds.

"There were times it seemed like it would be much easier to be dead," Saberi admits now, but she found the courage to hang on. "What kept me strongest was my belief that there must be someone or something looking down on me who cared about what was going to happen to me."

Indeed there was. Her parents had gotten the U.S. government involved, and CNN, the BBC, and the Associated Press reported on her plight. The Committee to Protect Journalists started a Facebook petition on her behalf, and Hillary Rodham Clinton called for her release. "[It] was a great shock...that anybody knew where I was and that they were making a lot of noise about it," says Saberi.

Evidently, the media outcry helped. After 100 days in Evin, on May 11, 2009, Saberi was finally freed, her punishment reduced to a two-year suspended sentence after she admitted to unwittingly possessing what the court called a classified document. Saberi and her parents flew to Washington, where she met with Secretary Clinton. "She said that as a mother, she could relate to the emotions my mother must have felt when I was imprisoned."

To this day, Saberi can only guess why the Iranian regime targeted her. "My captors knew I was going to leave the country soon, and they had invested a lot of money and energy into monitoring me," she says. "I think they didn't want me to share the views of people [I interviewed] in a way that they couldn't control."

Now recovering back home, Saberi is trying to put the ordeal behind her. "Some former prisoners walk down the street and wonder if someone is following them," she says. "Last night I dreamed that I was being told to wash the walls. I thought, Why am I back here?"

Freedom isn't something she will ever take for granted again. Saberi now plans to dedicate herself to human-rights advocacy and to finishing the book she started while living in Iran. "If I don't, it's a victory for my captors," she says. She doesn't want to give them the satisfaction.