Clive Barker, director

I worked as a hustler in the 1970s, because I had no money. I met a lot of people you’ll know and some you won’t: publishers, captains of industry. The way they acted – and the way I did, to be honest – was a source of inspiration later. Sex is a great leveller. It made me want to tell a story about good and evil in which sexuality was the connective tissue. Most English and American horror movies were not sexual, or coquettishly so – a bunch of teenagers having sex and then getting killed. Hellraiser, the story of a man driven to seek the ultimate sensual experience , has a much more twisted sense of sexuality.

By the mid-80s I’d had two cinematic abominations made from my stories. It felt as if God was telling me I should direct. How much worse could I be? I said to Christopher Figg, who became my producer: “What’s the least I could spend and expect someone to hire a first-time director?” And he said: “Under a million dollars. You just need a house, some monsters, and pretty much unknown actors.” My novella The Hellbound Heart, which mostly took place in one house, fitted those parameters. Roger Corman’s company New World – who agreed to fund a film for $900,000 – said very plainly it would go straight to video.

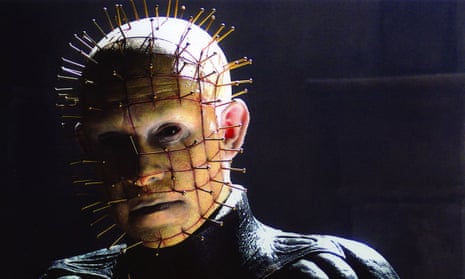

My film required some design elements that hadn’t been seen before, the equivalent of Freddy Krueger’s fedora, striped sweater and burnt face. The look of the Cenobites, such as the pins in their leader’s head, was inspired by S&M clubs. But I was emotionally inspired by them, too. On S&M’s sliding scale, I’m probably a 6. There was an underground club called Cellblock 28 in New York that had a very hard S&M night. No drink, no drugs, they played it very straight. It was the first time I ever saw people pierced for fun. It was the first time I saw blood spilt. The austere atmosphere definitely informed Pinhead: “No tears, please. It’s a waste of good suffering!”

The week before filming started, I went to the library at Crouch End, where I was living in London, to get a book about directing. They had one – but it was out. Luckily, the crew were very gentle with me. You can only go that far into darkness if everybody’s on board. I had Richard Marden, who had worked with David Lean, as editor, and Bob Keen, who had done special effects on Star Wars and came up with Frank’s resurrection scene. We had a nice working rhythm.

Initially, New World couldn’t care less. Then, about halfway through the six-week shoot, they said: “We’re coming over.” Robin Vidgeon, my director of photography, said: “I’ve seen this a million times. They see something they like and they want to take charge.” Three of them came over, all in new Burberry coats. Robin and I had changed the schedule so we were doing something incredibly bloody – one of them may have got their Burberry splashed, and they fled after 15 minutes. I didn’t get bothered by them again until later on. They got us to relocate the story to America, and overdub some of the accents – which I didn’t feel great about because the original story had been so English.

I wanted to call the movie Hellbound but Christopher said it was too negative. He suggested Hellraiser, which is exactly right. It’s about something coming at you. The American censors gave it an X rating, and to get an R we had to take some spanking out of the flashback scenes and shorten some of the violence.

New World gave it a wide release, and it made $33m worldwide. Pinhead was only in it for eight minutes, but it quickly became apparent people liked him. And I got a good reaction from the S&M crowd – and still do. I was validating a lifestyle. It was a celebration of the beauty of these strange secret rituals.

Doug Bradley, actor

I’d known Clive since we did a play together at high school in Liverpool. He first mentioned in the fall of 1985 that he was putting together a low-budget British independent horror movie. He said there might be a part for me – what became known as Pinhead. I was also offered the role of a removals man. For a split second, I had an actorly conversation with myself: because Hellraiser was my first movie, I thought it might be a good idea to be seen on screen as myself. But it was a brief conversation. There was no doubt in my mind that this unnamed guy with the pins in his head had a certain je ne sais quoi that a mattress-delivery guy didn’t.

The makeup took five or six hours to put on at first, though they got it down to three or four. The first time I wore it, I sat in front of the mirror trying to make friends with this new face, playing some lines and seeing where they took me. Most of my decisions about playing Pinhead were made there and then. I had a sense of power, of majesty, of a kind of beauty. His threat is implied: look what I did to myself – now imagine what I can do to you.

Clive was very excited to have his creations walking and talking around him. But he gave me one note. He said: “You have no idea how amazing this looks on camera. But do less.” So I would take things down a notch, and he would say the same thing again. He was leading me to realise that the makeup was so powerful, I didn’t need to sell it to the audience. It’s difficult as an actor because you feel as if you’re just standing still and saying words.

It was me on the poster when the film came out, and Pinhead was on the cover of Time Out. But I was not credited, and I didn’t do any publicity for the first film. However, when I came to the States for the first time in 1989 for a Fangoria horror convention, there was a line of fans going out of the hotel and round the corner. I assumed they were there for someone else, but it took me 20 minutes to get to my room because I was surrounded by people asking for photographs. That’s when I realised Pinhead had taken off with horror fandom. He represents the Faustian bargain: the things we desire will come at a price.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion