If Stephen Smartt gets lucky, he may one day receive a message that will give the astrophysicist an advance warning that one of the most extraordinary displays known to science is about to light up the night sky. Signals relayed by automated telescope arrays and underground detectors will reveal that a star in our galactic neighbourhood has just turned supernova.

A supernova occurs when a star destroys itself so completely it can outshine the combined light of an entire galaxy. In the last thousand years, only five have ever been visible to the naked eye. Ironically, all occurred before the invention of the telescope.

“We know about supernovae from their appearance in other galaxies and from remnants left behind in our own galaxy,” says Smartt, an astrophysicist based at Queen’s University Belfast. “But what we would love to do is see one that appears fairly near us so we can study it with modern telescopes and detectors.”

When a supernova erupts, it sprays the cosmos with heavy elements – so observing one nearby would provide precious information about the creation of matter in our galaxy.

“Most elements heavier than oxygen were created in a supernova before being hurled across space,” says Prof Mark Sullivan of the University of Southampton. “These atoms provide the galaxy with material essential to life. The calcium in your bones and the iron in your blood – as well as the gold in the ring on your finger – were all created in supernovae explosions.”

It is an image that continues to entrance writers and artists. In Jeanette Winterson’s words, astronomers have shown our first true parent was actually a star and that we are made of elements that are “the long-lived radioactive nuclear waste of the supernova bang”. Or, as Joni Mitchell put it, more simply: “We are stardust.”

The most common type of supernova occurs when a very large star runs out of fuel, halting the nuclear fusion process that keeps it shining. The star’s outer layers fall inwards, and protons and electrons are crushed together to form neutrons that become packed into a superdense ball. Matter continues to rain down on this neutron ball before bouncing back, triggering a shock wave that destroys the star.

All that is left behind is a neutron sphere that is so dense a matchbox of it would weigh about 3bn tonnes. And if the original progenitor star that led to the supernova was particularly large, this neutron star will become so heavy it will form a black hole from which nothing can escape, not even light.

This is a core-collapse supernova and it can unleash more energy than our sun will release over its entire 10bn-year lifetime. If a star in our galaxy, too distant to be seen by the naked eye on Earth, becomes a supernova, it will suddenly shine so brilliantly it could be seen in daylight.

Scientists estimate that on average about 20 supernovae occur in a galaxy such as ours every thousand years. Yet only five have been observed in the last millennium. East Asian and Arabic records indicate there were supernovae in 1006, 1054 and 1181, while European documents recall ones that occurred in 1572 and 1604.

The first of this last pair flashed into sight in November 1572 and was observed by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. “Overhead, a certain strange star was suddenly seen, flashing its light with a radiant gleam,” he recalled. “I stood still, gazing … When I had satisfied myself that no star of that kind had ever shone forth before, I was led into such perplexity by the unbelievability of the thing that I began to doubt the faith of my own eyes.”

But if supernovae are so brilliant, why have we only detected five in the past 1,000 years? Why have we not seen a number that is nearer the 20 suggested by observations of other galaxies? The answer is straightforward, says Sullivan. “Our galaxy is like a flat plate and our solar system is about two-thirds of the way towards its edge. A supernova that occurs on the other side of the plate will simply be obscured by all the dust and stars that lie at the centre of the galaxy.”

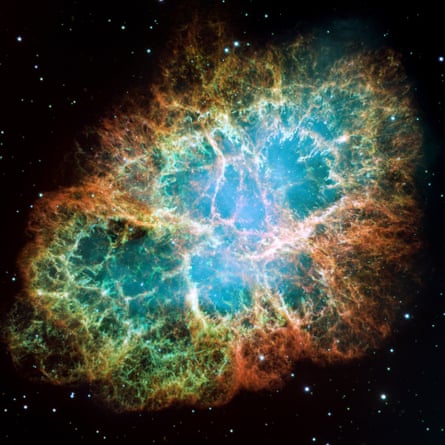

Astronomers have since observed supernovae in other galaxies and studied remnants of those that have occurred inside our galaxy. These include the glowing filaments of the Crab Nebula, the remains of the supernova that lit up night skies in 1054AD and which have since been spreading across space.

Galactic debris such as this reveals the enormous destruction that is unleashed by supernovae. Yet these stellar convulsions are also important engines of creation, scientists argue. Apart from spraying the cosmos with heavy elements on which life depends, they also play a key role in planet and star formation, says astrophysicist Cosimo Inserra of Cardiff University.

“A supernova sends shock waves across a galaxy and these strike clouds of gas and dust in space, compressing them so that proto-stars start to form at their centres. Eventually, nuclear fusion begins, igniting a star’s store of hydrogen and it starts to shine. Planets form and orbit the star. That is probably how our sun and solar system came into existence.”

Supernovae do pose threats, nevertheless. “If one occurred within 20 parsecs – roughly 60 light years – of the Earth, its intense cosmic rays could destroy our protective ozone layer, which would allow increased levels of ultraviolet radiation from the sun to reach us,” says Sullivan. However, only one very close to Earth could have such an impact and at present there are no candidate stars near us that look ready to annihilate themselves this way, he adds.

On the other hand, it is also clear supernovae have exploded near Earth in the past. As evidence, scientists point to the discovery of a radioactive isotope of iron – known as iron-60 – that has been found in seabed deposits laid down 2.5m years ago and in other deposits created about 7m years ago. Iron-60 is produced by supernovae and these deposits suggest at least two must have erupted near Earth within the last 10m years, probably at a distance of about 100 parsecs, or 320 light years.

What impact that had on the planet is uncertain. “You might have had a rise in cosmic-ray activity and this might have affected cloud formation on Earth or reduced the amount of solar radiation reaching the ground,” says Prof John Ellis of King’s College London. “This could then have triggered a change in the climate, which in turn could have affected the course of human evolution.”

Apart from the rather startling prospect that the appearance of Homo sapiens might have been shaped by local supernovae, these discoveries also suggest there might have been enough of them to have had a real influence on life earlier in our planet’s history.

“If you find two that happened fairly near Earth within the past 10m years, that suggests hundreds must have appeared over the past billion years,” argues Ellis. “Some of them will have been quite distant … but a few would have been close, say 10 parsecs away. And we should be clear: if a supernova went off within 10 parsecs of our planet, it would very likely have caused a mass extinction.”

Earth has experienced at least five mass extinctions that have each eradicated thousands of species of animals, plants and sea creatures, and at least one of these was caused by an extraterrestrial agent: an asteroid that struck Earth at the end of the Cretaceous period 66m years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs.

Earth-based catastrophes – such as large-scale volcanism – have been blamed for the other mass extinctions. However, scientists now suspect that in one other case, an otherworldly event was to blame. They point to rocks that formed at the end of the Devonian period 360m years ago when there was another mass extinction that wiped out ammonites, trilobites and other early forms of life.

These rocks contain hundreds of thousands of generations of plant spores that appear to be sunburnt by ultraviolet light – evidence of a long-lasting ozone-depletion event, says astronomer Brian Fields at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “We propose that one or more supernova explosions, about 65 light years from Earth, could have been responsible for the protracted loss of ozone,” he argues.

This blast would have first bathed Earth with powerful X-rays and gamma rays before debris from the blast slammed into the planet, stripping it of its protective ozone layer. This astronomical double whammy would have exposed the planet’s surface to deadly radiation for up to 100,000 years and led to a mass extinction.

Further proof for this idea is now being sought by scientists. They have discounted looking for iron-60 atoms because these decay too quickly to have survived the 360m years since the late Devonian mass extinction. Instead, they plan to seek out atoms of the isotope plutonium-244, which is also produced by supernovae and could survive for a few hundred million years. That research is now under way.

In the meantime, scientists are preparing themselves to react as speedily as possible to the first signs that a nearby supernova has begun. Crucially, these first signals will not come flashes of light but will emerge from underground detectors designed to spot the universe’s most insignificant entity, the neutrino.

“Neutrinos are the first thing that will emerge from a supernova,” says Smartt. “They are so insubstantial, they are very difficult to detect and instruments have to be put in places where they do not pick up spurious signals from other sources.

“However, if enough are detected, then an automated alert will be sent out and the arrays of telescopes that we use to study the night sky will be turned towards the sources of those neutrinos. Then we will be ready to study the first bursts of radiation and light emerging from the supernova and to watch how it unfolds.”

While scientists are confident a supernova will occur in 2022, whether it occurs in our galaxy is a different matter. In any given year, it is an unlikely prospect. On the other hand, one day it may just happen in our galactic neighbourhood. If it does, astronomers say they will be ready.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion