Advertisement

How Cape Ann, a lost cat and a meet-cute catalyzed artist Edward Hopper's career

Resume

There's a good chance you've seen Edward Hopper's quietly dramatic landscapes and scenes of ordinary life. "Nighthawks," his painting of a luminescent, late-night diner is iconic. But it took time for the now legendary 20th-century artist to find his visual voice. A new exhibition at the Cape Ann Museum, "Edward Hopper & Cape Ann: Illuminating an American Landscape," transports visitors back to a pivotal summer, 100 years ago, when Hopper met the woman who catalyzed his creativity and his career.

Curator Elliot Bostwick Davis unfolded the tale as dozens of canvases, drawings and prints were being installed in the museum's gallery. In the early 1900s, New York artists flocked to Gloucester's coast hoping to capture its picturesque geography, seaswept structures and coveted clarity of light.

It was 1923 when the then little-known Edward Hopper returned to the Massachusetts coast by train. At 41 years old, he was hungry for recognition and felt rather desperate. “He's only sold one painting over a decade earlier,” Davis said. “He knows he's really gotta make or break it. He's been persevering, but he hasn't managed to break through.”

Another artist was also in town with her brushes. Forty-year-old Josephine Nivison had crossed paths with Hopper on previous New England painting trips. While they shared the same influential teacher, Robert Henri, the two artists studied apart in classes separated by gender. But they finally got to “meet cute” formally, thanks to Nivison's feline traveling companion.

“Her cat Arthur escaped onto the back streets of Gloucester,” Davis recounted. “So the story goes Edward Hopper — whether he captured Arthur, whether he found Arthur, is unclear — but Arthur was returned to a very grateful Jo Nivison.”

Like Hopper, Nivison was single. But, in many ways, they made an unlikely pair.

“He was over 6'4", almost 6'5", she was just a little over 5 feet,” Davis said. “She was incredibly gregarious. In addition to painting and drawing, she loved to dance, was an amateur thespian, was very independent.”

Nivison would later describe Hopper as being reserved. “When you spoke with Edward Hopper it was like putting a stone down a well, but you never heard a drop.”

When Hopper reunited Nivison and her cat, he also gave her a hand-drawn map of Gloucester. Their courtship sparked with painting excursions around the city. He usually used oils. Then Nivison asked him to try watercolor. “It was one of the popular mediums,” Davis said, “and it was her favorite.”

Turns out Nivison's suggestion was pivotal. Now a trove of the duo's watercolors are among 66 works in the new exhibition, “Edward Hopper & Cape Anne: Illuminating an American Landscape.”

Museum Director Oliver Barker is thrilled to host dozens of loans from 27 private collectors and institutions. He said an unprecedented partnership with the Whitney Museum of American Art that includes 28 borrowed artworks has been key for Davis' deep dive into Hopper's formation. “I think this provides, thanks to [her] brilliant scholarship, a new way of looking at Edward Hopper — an artist that we all think we know.”

Outside the gallery's entrance, a period map from the museum's archive depicts key spots where Hopper and Nivison painted. If visitors are game, they can set out on something of a scavenger hunt around Gloucester, matching the locations to works in the show.

Barker and Davis were happy to play tour guides, so we headed out to follow in the couple's footsteps. With gulls squawking overhead, we passed ornate Victorian homes, an old granite staircase and a church with two bell towers near the museum that caught the artists' eyes.

“In 1923, Edward Hopper and Jo Nivison must have come down here to this street corner to paint Our Lady of Good Voyage,” Davis said. Nivison focused on the building's animated curves and front facade. Hopper went around back. "He was often a contrarian," Davis added. "They're seeing it from two distinct perspectives and personalities." Nivison also preferred paintings on a vertical sheet of paper. Hopper chose horizontal.

According to Davis, Nivison's free spirit was attracted to the sometimes wayward fluidity of watercolors. But for Hopper, who'd previously worked with more easily controlled oils, this type of expression was new. Barker said, “He was building up his confidence with watercolor as a medium.”

“She definitely has a different kind of artistic practice,” Davis added, "which I think helps [Hopper] see his way to becoming more of himself, and I think the spontaneity that Jo was after was really helpful to him.”

After a summer of painting dates, Nivison would go on to help launch Hopper's career. She asked the Brooklyn Museum to include her beau's work in an important, American watercolor show she was slated to show in that fall of 1923. And she made a generous sacrifice. “She gave up six of her slots, so that six of his pieces should be shown,” Barker said.

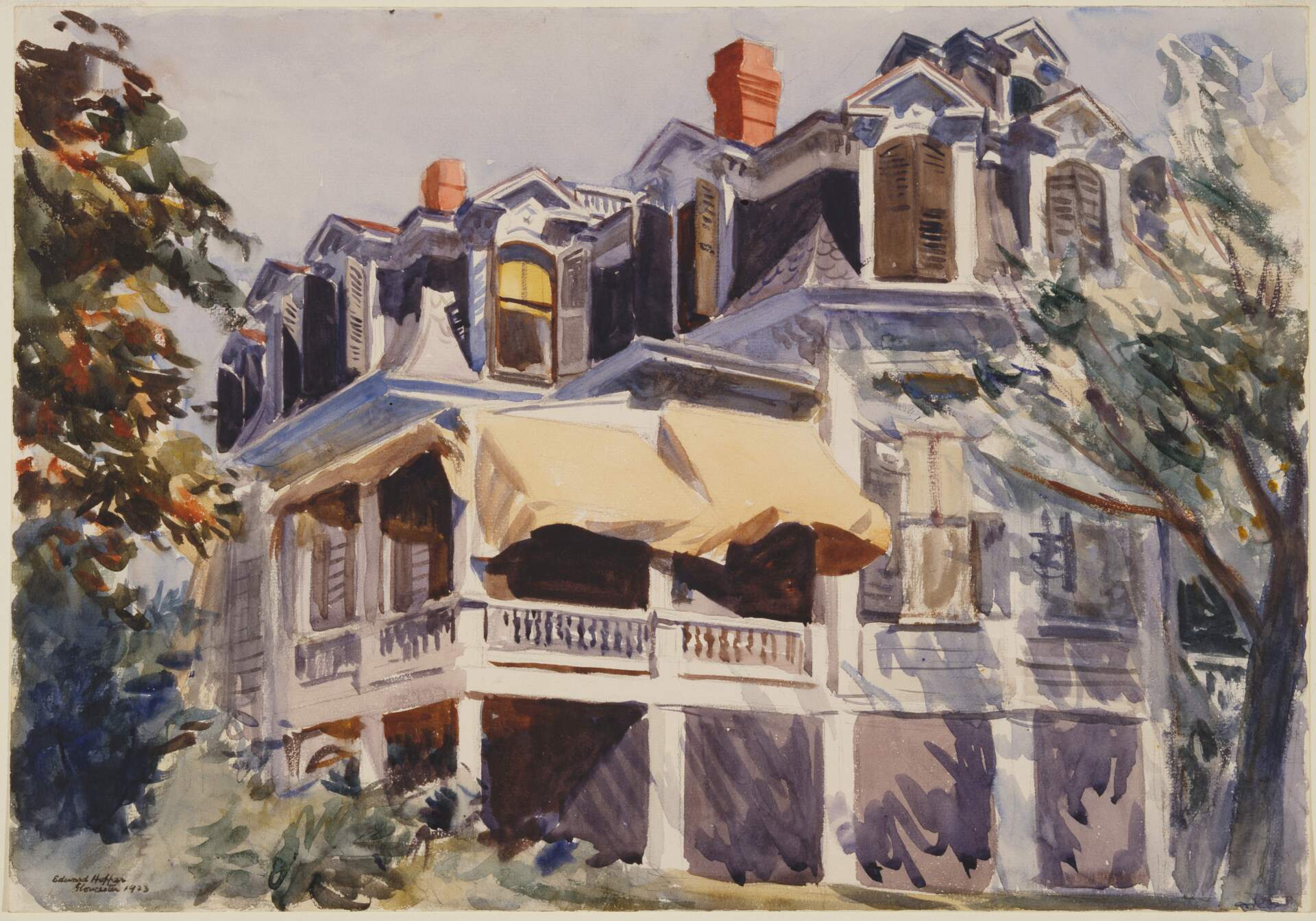

The Brooklyn Museum ended up buying Hopper's Cape Ann watercolor titled “The Mansard Roof,” which introduced his new style to the art world.

After this big break, Nivison hoped to spend the following summer in Provincetown. But Hopper was set on Gloucester.

“They have a huge argument,” Davis said, then Nivison issued an ultimatum. "She told Hopper, 'I'll go on one condition — that we get married today.” That day was July 9, 1924.

Nivison became Hopper's sole model, muse and manager of his career. Davis uses the word “producer” to describe her role in his trajectory and "brand." Nivison also kept a detailed log book of Hopper's work that's served as a critical record of his legacy.

Like so many 20th-century artists/wives, Nivison gave up exhibiting for a time, in part, because the art world wasn't as interested in her work.

“She was certainly pragmatic, and I think she knew that her watercolors sold for much less, even when she was showing them,” Davis said. “And if she could make sure that Edward Hopper was able to continue to paint, he would have a very successful career.”

Nivison was right. And while 57 of her famous husband's works fill this exhibition, the centerpiece gallery belongs to her. “This we think of as Jo's space,” Davis said with a smile.

A few Nivison watercolors of Cape Ann hang on the blue room's walls, along with three stunning portraits. Her teacher Robert Henri captured Nivison as a promising, 19-year-old art student. Hopper made an oil painting of his wife when she was about 50. We stood back as assistant curator Leon Doucette hung a self-portrait Nivison executed in her 70s. Once level on the wall, Barker gushed, “It's fantastic.”

“The idea was to really have her speaking to her earlier selves as she changes,” Davis said of the trio positioned on opposite walls. “I also think it's extraordinary that you don't usually think of women of this generation painting themselves this way.”

Wearing a sheer, pink negligee, Nivison's likeness stares out from the canvas with a confident gaze. She stood in for the human figures in her husband's paintings throughout their partnership. But Davis said Nivison never stopped making her own works and had her first, full-scale show in New York in 1958.

Barker hopes Nivison would be pleased with this homecoming for so many paintings she and Hopper made at sites so close to the museum. And, he added, Nivison visited the Cape Ann institution when it first opened as a historical society in 1926. She was the last person on the last day of that summer to sign the guest book. "So, we know that she was here," Barker said. "And it's very exciting now, almost a hundred years on, that we're actually putting her own work in these spaces.”

The Cape Ann Museum's celebration of Nivison's often overlooked legacy opens Saturday, July 22, which, fittingly, is also Edward Hopper's birthday.

This segment aired on July 21, 2023.