Migration and breeding biology of Arctic terns in Greenland

Migration and breeding biology of Arctic terns in Greenland

Migration and breeding biology of Arctic terns in Greenland

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

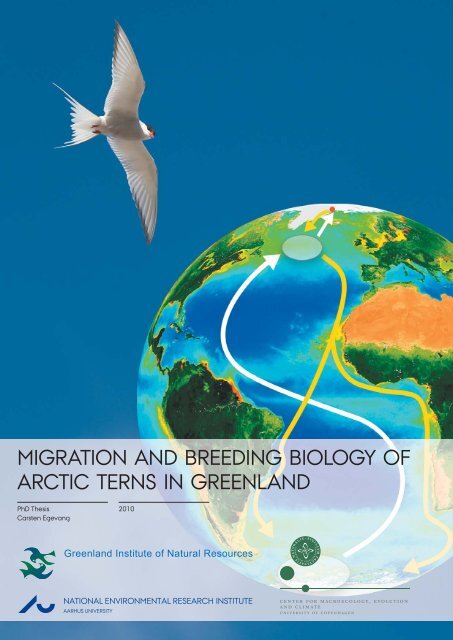

MIGRATION AND BREEDING BIOLOGY OF<br />

ARCTIC TERNS IN GREENLAND<br />

PhD Thesis 2010<br />

Carsten Egevang<br />

AU<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources<br />

NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE<br />

center for macroecology, evolution<br />

a nd climate<br />

AARHUS UNIVERSITY university <strong>of</strong> copenhagen

AU<br />

MIGRATION AND BREEDING BIOLOGY OF<br />

ARCTIC TERNS IN GREENLAND<br />

PhD Thesis 2010<br />

Carsten Egevang<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources<br />

NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE<br />

AARHUS UNIVERSITY<br />

center for macroecology, evolution<br />

<strong>and</strong> climate<br />

university <strong>of</strong> copenhagen

Title: <strong>Migration</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

Subtitle: PhD Thesis<br />

Author: Carsten Egevang<br />

Affi liation: Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources<br />

Dep. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> Environment, National Environmental Research Institute, Aarhus University<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Biology, Center for Macroecology, Evolution <strong>and</strong> Climate, University <strong>of</strong> Copenhagen<br />

Publisher: Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources <strong>and</strong> National Environmental Research Institute (NERI)©<br />

Aarhus University – Denmark<br />

URL: http://www.neri.dk<br />

Date <strong>of</strong> publication: March 2010<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ancial support: Commission for Scientifi c Research <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> (KVUG)<br />

Please cite as: Egevang, C. 2010: <strong>Migration</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. PhD thesis. Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute<br />

<strong>of</strong> Natural Resources, Dep. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> Environment, NERI, Aarhus University & Department <strong>of</strong> Biology,<br />

Center for Macroecology, Evolution <strong>and</strong> Climate, University <strong>of</strong> Copenhagen. Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural<br />

Resources & National Environmental Research Institute, Aarhus University, Denmark. 104 pp.<br />

Reproduction permitted provided the source is explicitly acknowledged.<br />

Abstract: This thesis presents novel fi nd<strong>in</strong>gs for the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. Included is a study on <strong>Arctic</strong> tern migration<br />

– the longest annual migration ever recorded <strong>in</strong> any animal. The study documented how Greenl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Icel<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>terns</strong> conduct the roundtrip migration to the Weddell Sea <strong>in</strong> Antarctica <strong>and</strong> back. Although the sheer<br />

distance (71,000 km on average) travelled by the birds is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g, the study furthermore showed how the<br />

birds depend on high-productive at-sea areas <strong>and</strong> global w<strong>in</strong>d systems dur<strong>in</strong>g their massive migration.<br />

Furthermore <strong>in</strong>cluded is the fi rst quantifi ed estimate <strong>of</strong> the capacity to produce a replacement clutch <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong><br />

<strong>terns</strong>. We found that approximately half <strong>of</strong> the affected birds would produce a replacement clutch when the<br />

eggs were removed late <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>cubation period.<br />

At a level <strong>of</strong> more national <strong>in</strong>terest, the study produced the fi rst estimates <strong>of</strong> the key prey species <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong><br />

tern <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. Although zooplankton <strong>and</strong> various fi sh species were present <strong>in</strong> the chick diet <strong>of</strong> <strong>terns</strong><br />

<strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Disko Bay, Capel<strong>in</strong> was the s<strong>in</strong>gle most important prey species found <strong>in</strong> all age groups <strong>of</strong> chicks.<br />

The thesis also <strong>in</strong>cludes a study on the fl uctuat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> found <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong>. Breed<strong>in</strong>g birds showed a<br />

considerable variation <strong>in</strong> colony size between years <strong>in</strong> the small <strong>and</strong> mid sized colonies <strong>of</strong> Disko Bay. These<br />

variations were likely to be l<strong>in</strong>ked to local phenomena, such as disturbance from predators, rather than to<br />

large-scale occurr<strong>in</strong>g phenomena.<br />

Included is also a study that documents the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> association between <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> <strong>and</strong> other <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

waterbirds. At Kitsissunnguit a close behavioural response to tern alarms could be identifi ed. These fi nd<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

imply that the altered distributions <strong>of</strong> waterbirds observed at Kitsissunnguit were governed by the distribution<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong>.<br />

Included <strong>in</strong> the thesis are furthermore results with an appeal to the Greenl<strong>and</strong> management agencies. Along<br />

with estimates <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population size at the two most important <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies <strong>in</strong> West Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> East Greenl<strong>and</strong>, the study produced recommendations on how a potential future susta<strong>in</strong>able egg<br />

harvest could be carried out, <strong>and</strong> on how to monitor <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Keywords: At-sea hot-spots, <strong>Arctic</strong>, <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> association, <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> ecology, <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> fl uctuation, colony attendance,<br />

diet, egg harvest, global w<strong>in</strong>d systems, long-distance migration, nature management, Sterna paradisaea,<br />

replacement clutch.<br />

Supervisors: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Carsten Rahbek, Department <strong>of</strong> Biology, Center for Macroecology,<br />

Evolution <strong>and</strong> Climate, University <strong>of</strong> Copenhagen.<br />

Senior advisor Dr. Morten Frederiksen, Dep. <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> Environment,<br />

National Environmental Research Institute, Aarhus University.<br />

Dr. Norman Ratcliffe, British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council.<br />

Layout: T<strong>in</strong>na Christensen<br />

Frontpage: Carsten Egevang<br />

ISBN: 87-91214-46-7<br />

ISBN (DMU): 978-87-7073-166-9<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted by: Rosendahls – Schultz Grafi sk a/s<br />

Number <strong>of</strong> pages: 104<br />

Circulation: 100<br />

Data sheet<br />

Internet version: The report is available <strong>in</strong> electronic format (pdf) at NERI’s website<br />

http://www.dmu.dk/Pub/PHD_CEP.pdf

Content<br />

List <strong>of</strong> publications/manuscripts <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the thesis 5<br />

Preface 6<br />

Acknowledgements 8<br />

Summary 9<br />

Dansk resumé 11<br />

Eqikkaaneq 13<br />

1 Synopsis 15<br />

1.1 Introduction 15<br />

1.2 Objectives 16<br />

1.3 Distribution 16<br />

1.4 Population status <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> 16<br />

1.5 Population status at Kitsissunnguit 17<br />

1.6 Fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> 17<br />

1.7 Plausible cause <strong>of</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> population size 18<br />

1.8 Renest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> 19<br />

1.9 Variation <strong>in</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> phenology 20<br />

1.10 Clutch size 21<br />

1.11 Hatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> fl edg<strong>in</strong>g success 21<br />

1.12 Growth rate <strong>and</strong> chick survival 22<br />

1.13 Feed<strong>in</strong>g 23<br />

1.14 Breed<strong>in</strong>g association 24<br />

1.15 <strong>Migration</strong> 25<br />

2 Conclusion 29<br />

3 Future research 30<br />

4 References 31<br />

Manus I 35<br />

Manus II 41<br />

Manus III 57<br />

Manus IV 85<br />

Manus V 97

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS/MANUSCRIPTS<br />

INCLUDED IN THE THESIS<br />

Egevang, C., I.J. Stenhouse, R.A. Phillips, A. Petersen, J.W. Fox & J.R.D.<br />

Silk (2010). Track<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> Sterna paradisaea reveals longest<br />

animal migration. Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> the National Academy <strong>of</strong> Sciences <strong>of</strong><br />

the United States. Vol. 107: 2078-2081 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0909493107).<br />

Egevang, C., N. Ratcliffe & M. Frederiksen. Susta<strong>in</strong>able regulation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Arctic</strong> tern egg harvest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. Manuscript.<br />

Egevang, C., M. W. Kristensen, N. Ratcliffe & M. Frederiksen. Food-related<br />

consequences <strong>of</strong> relay<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> Tern: Contrast<strong>in</strong>g prey availability<br />

with<strong>in</strong> a prolonged <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> season. Manuscript submitted IBIS.<br />

Egevang, C. & M. Frederiksen. Fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> Terns (Sterna<br />

paradisaea) <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>and</strong> High-arctic colonies <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. Manuscript<br />

submitted WATERBIRDS.<br />

Jørgensen, P. S., Kristensen, M. W. & Egevang, C. 2007. Red Phalarope<br />

Phalaropus fulicarius <strong>and</strong> Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus lobatus<br />

behavioural response to <strong>Arctic</strong> Tern Sterna paradisaea colonial alarms.<br />

Dansk Ornitologisk Foren<strong>in</strong>gs Tidsskrift 101 (3): 73-78, 2007.<br />

5

6<br />

Preface<br />

This thesis is the result <strong>of</strong> my PhD conducted at the University <strong>of</strong> Copenhagen,<br />

Center for Macroecology, Evolution <strong>and</strong> Climate (UC), Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources (GINR) <strong>and</strong> National Environmental Research<br />

Institute, Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> Environment (NERI). The PhD was<br />

fi nancially supported by Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources (GNIR)<br />

<strong>and</strong> the Commission for Scientifi c Research <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> (KVUG). The<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciple supervisor was Carsten Rahbek (UC) whereas Morten Frederiksen<br />

(NERI) <strong>and</strong> Norman Ratcliffe (British Antarctic Survey) functioned as<br />

external supervisors.<br />

The pre-2002 level <strong>of</strong> knowledge on the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> was rather<br />

low <strong>and</strong> even rather basic biological <strong>in</strong>formation was unavailable for<br />

the species. On the other side there’s an urgent need for more <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Greenl<strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> the liv<strong>in</strong>g resources <strong>and</strong> protected areas.<br />

This lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge has been decisive <strong>in</strong> my cho ice <strong>of</strong> study species,<br />

study topic <strong>and</strong> study location at the plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> my PhD. It has been both<br />

a strong motivation factor for me throughout my PhD, but also frustrat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

at times where the lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation made it diffi cult to approach topics<br />

from a theoretical po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view.<br />

Although my PhD <strong>of</strong>fi cially started mid 2004, my work on <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> is really a cont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>of</strong> fi eldwork conducted <strong>in</strong> 2002 <strong>and</strong><br />

2003. Concurrently with my PhD I have worked as seabird researcher at<br />

GNIR, where I have been responsible for monitor<strong>in</strong>g seabirds <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> ad-hoc advis<strong>in</strong>g the Greenl<strong>and</strong> Government <strong>in</strong> a susta<strong>in</strong>able<br />

use <strong>of</strong> the liv<strong>in</strong>g resources. For this reason the delivery date <strong>of</strong> my PhD<br />

has been prolonged to March 2010 – more than one year later than fi rst<br />

scheduled. Along the course <strong>of</strong> my PhD the topic <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the PhD<br />

got extended. The technology <strong>in</strong> track<strong>in</strong>g devices for small-sized seabirds<br />

advanced <strong>and</strong> from deal<strong>in</strong>g only with <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> ecology <strong>and</strong> census<strong>in</strong>g<br />

methods, my PhD got extended to <strong>in</strong>clude migration ecology as well.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g my PhD I have been physically placed <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> at GINR until<br />

May 2008, where my family <strong>and</strong> I moved to Denmark <strong>and</strong> NERI was k<strong>in</strong>d<br />

enough to <strong>of</strong>fer me a work seat.<br />

The fi eldwork <strong>in</strong> connection with my PhD was conducted at two very<br />

different fi eld sites <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>: Kitsissunnguit (Grønne Ejl<strong>and</strong>) dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

2002 to 2006 <strong>in</strong> the southern part <strong>of</strong> Disko Bay <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> zone <strong>in</strong> West<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> at S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong> (S<strong>and</strong>øen) dur<strong>in</strong>g 2007 <strong>and</strong> 2008 <strong>in</strong> high<br />

<strong>Arctic</strong> Northeast Greenl<strong>and</strong> (see fi gure 1-3).<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g my PhD I have produced papers, reports or book contributions as<br />

a sp<strong>in</strong>-<strong>of</strong>f from the work on <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> conducted dur<strong>in</strong>g my PhD. These<br />

are not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> my PhD thesis but are listed here:<br />

Egevang, C. & D. Boertmann 2008. “Ross’s Gulls (Rhodostethia rosea) <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>: A Review, with Special Emphasis on Records from<br />

1979 to 2007.” <strong>Arctic</strong> 61(3): 322-328.

Egevang, C. Kampp, K. & Boertmann D. 2006. ”Decl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

waterbirds follow<strong>in</strong>g a redistribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> Terns Sterna paradisaea <strong>in</strong><br />

West Greenl<strong>and</strong>” Waterbirds around the World. Eds. G. C. Boere, C. A.<br />

Galbraith & D. A. Stroud. The stationery Offi ce, Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh, UK. P. 154<br />

(http://www.jncc.gov.uk/PDF/pub07_waterbirds_part3.3.1.6.pdf).<br />

Egevang, C. , K. Kampp & D. Boertmann 2004 “The Breed<strong>in</strong>g Association<br />

<strong>of</strong> Red Phalaropes (Phalaropus fulicarius) with <strong>Arctic</strong> Terns (Sterna<br />

paradisaea): Response to a Redistribution <strong>of</strong> Terns <strong>in</strong> a Major Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

Colony” Waterbirds 27 (4): 406-410.<br />

Egevang, C., I. J. Stenhouse, L. M. Rasmussen, M. W. Kristensen <strong>and</strong> F.<br />

Ugarte 2009. ”Breed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> forag<strong>in</strong>g ecology <strong>of</strong> seabirds on S<strong>and</strong>øen<br />

2008”. <strong>in</strong> Jensen, L.M. & Rasch, M. (eds.) 2009: Zackenberg Ecological<br />

Research Operations, 14 th Annual Report, 2008. National Environmental<br />

Research Institute, Aarhus University, Denmark. 116 pp.<br />

Egevang, C., I. J. Stenhouse, Lars Maltha Rasmussen, Mikkel Willemoes<br />

& Fern<strong>and</strong>o Ugarte 2008. “Field report from S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>, Northeast<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong>, 2008. http://www.natur.gl/UserFiles/File/feltrapporter/<br />

Fieldreport_%20S<strong>and</strong>Isl<strong>and</strong>_2008_fi nal.pdf.<br />

Egevang, C. 2008. ”Forstyrrelser i grønl<strong>and</strong>ske havfuglekolonier, med speciel<br />

fokus på ynglende havterner på Kitsissunnguit (Grønne Ejl<strong>and</strong>),<br />

Disko Bugt”. Teknisk rapport nr. 71, Grønl<strong>and</strong>s Natur<strong>in</strong>stitut, 21 sider.<br />

http://www.natur.gl/UserFiles/File/Publlikationer/2008-02_GN_teknisk_rapport_71_fi<br />

nal_forstyrrelser_fuglekolonier.pdf<br />

Egevang, C. & Stenhouse, I. J. 2008. Mapp<strong>in</strong>g long-distance migration <strong>in</strong><br />

two <strong>Arctic</strong> seabird species p. 74-76. In: Klitgaard, A.B. <strong>and</strong> Rasch, M.<br />

(eds.) 2008. Zackenberg Ecological Research Operations, 13 th Annual Report,<br />

2007. Danish Polar Center, Danish Agency for Science, Technology<br />

<strong>and</strong> Innovation, M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Science, Technology <strong>and</strong> Innovation, 2008.<br />

http://www.zackenberg.dk/graphics/Design/Zackenberg/Publications/English/Zero%202007.pdf<br />

Egevang, C. & I. J. Stenhouse 2007. ”Field report from S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>, Northeast<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong>, 2007”. http://www.natur.gl/UserFiles/File/feltrapporter/Fieldwork_S<strong>and</strong>_Isl<strong>and</strong>_2007_1.pdf<br />

Egevang, C., D. Boertmann & O. S. Kristensen 2005 ”Moniter<strong>in</strong>g af<br />

havternebest<strong>and</strong>en på Kitsissunnguit (Grønne Ejl<strong>and</strong>) og den sydlige<br />

del af Disko Bugt, 2002-2004”. Teknisk rapport nr. 62, Grønl<strong>and</strong>s Natur<strong>in</strong>stitut,<br />

41 p. http://www.natur.gl/fi ler/Havternemoniter<strong>in</strong>g.pdf<br />

The study on the migration <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern <strong>in</strong>cluded novel fi nd<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong><br />

had appeal to a broad public audience. Therefore I build a web site (www.<br />

arctictern.<strong>in</strong>fo) especially dedicated to the communication <strong>of</strong> the results<br />

orig<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g from our study.<br />

My thesis deals with an array <strong>of</strong> different topics with<strong>in</strong> the fi eld <strong>of</strong> ecology.<br />

From small-scale issues, like egg harvest<strong>in</strong>g by local Inuit at the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

grounds, to large-scale occurr<strong>in</strong>g phenomena, such as global w<strong>in</strong>d systems<br />

<strong>and</strong> global mar<strong>in</strong>e biological productivity. Although, it may seem<br />

like a confl ict<strong>in</strong>g cocktail <strong>of</strong> topics, it is all focused on the same species –<br />

the gracious <strong>Arctic</strong> tern.<br />

7

8<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

I owe tremendous thanks to my external supervisor Morten Frederiksen<br />

(NERI) who has provided excellent guidance <strong>and</strong> supervision – not once<br />

did I experience that Morten couldn’t fi nd the time to support me <strong>in</strong> technical<br />

matters <strong>and</strong> give me <strong>in</strong>put <strong>in</strong>stantly. Also thanks to Norman Ratcliffe<br />

(British Antarctic Survey), my other external supervisor for help modell<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the data obta<strong>in</strong>ed over the fi eld seasons.<br />

The Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural Resource provided the framework to<br />

work with my thesis on the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern – both <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Denmark.<br />

For that I’m most grateful to the director Klaus Nygaard <strong>and</strong> head <strong>of</strong> department<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Ugarte. Also thanks to Jesper Madsen, head <strong>of</strong> department<br />

<strong>and</strong> Anders Mosbech, head <strong>of</strong> section for their will<strong>in</strong>gness to<br />

provide me with a disk at the crowed <strong>Arctic</strong> Environment department at<br />

NERI.<br />

Special thanks goes to Scottish friend <strong>and</strong> colleague Ia<strong>in</strong> Stenhouse (National<br />

Audubon Society) who endured cold <strong>and</strong> stormy days with me <strong>in</strong><br />

a tent at S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> gave <strong>in</strong>valuable language comments to this<br />

synopsis.<br />

My thanks goes to the people who assisted me <strong>in</strong> the fi eld over the years:<br />

David Boertmann <strong>and</strong> Morten Bjerrum (National Environmental Research<br />

Institute, Denmark), Anders Tøttrup, Mikkel Willemoes <strong>and</strong> Peter S. Jørgensen<br />

(University <strong>of</strong> Copenhagen), Lars Maltha Rasmussen, Fern<strong>and</strong>o<br />

Ugarte, Ole S. Kristensen, Lars Witt<strong>in</strong>g, Kate Skjærbæk Rasmussen <strong>and</strong><br />

Rasmus Lauridsen (GNIR), Bjarne Petersen, Qasigiannguit <strong>and</strong> Norman<br />

Ratcliffe <strong>and</strong> Stuart Benn (Royal Society for Protection <strong>of</strong> Birds). Also<br />

thanks to F<strong>in</strong>n Steffens (Qeqertarsuaq) <strong>and</strong> Elektriker-it (Aasiaat) for<br />

logistic support <strong>in</strong> Disko Bay, <strong>and</strong> to the Danish Polar Centre, Zackenberg<br />

Ecological Research Operations, POLOG, <strong>and</strong> Sledge Patrol Sirius<br />

<strong>and</strong> Nette Levermann (Greenl<strong>and</strong> Government) for logistic assistance <strong>in</strong><br />

Northeast Greenl<strong>and</strong> (S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>).<br />

I will also like this opportunity to thank the local <strong>in</strong>habitants <strong>of</strong> Disko Bay.<br />

Through arranged meet<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> Aasiaat <strong>and</strong> multiple opportunistic visits<br />

at our fi eld camp at Kitsissunnguit, they have thought me another view at<br />

harvest<strong>in</strong>g natural resources <strong>and</strong> the signifi cance <strong>of</strong> this.<br />

Last, but certa<strong>in</strong>ly not least, I would like to thank my family, my wife Inge<br />

Thaulow <strong>and</strong> my two boys Emil <strong>and</strong> Peter, for patience, underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> absents dur<strong>in</strong>g fi eldwork – THANKS!

Summary<br />

This PhD thesis presents the results <strong>of</strong> a study performed on the <strong>Arctic</strong><br />

tern (Sterna paradisaea) <strong>in</strong> the period 2002-2008. Data <strong>in</strong> the study were obta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

from fi eldwork conducted at two study sites <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>: Kitsissunnguit<br />

(Grønne Ejl<strong>and</strong>), Disko Bay <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> West Greenl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> S<strong>and</strong><br />

Isl<strong>and</strong> (S<strong>and</strong>øen) <strong>in</strong> high-<strong>Arctic</strong> Northeast Greenl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

The level <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> before 2002 was to<br />

a large extent poor, with aspects <strong>of</strong> its <strong>biology</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g completely unknown<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Greenl<strong>and</strong> population. This thesis presents novel fi nd<strong>in</strong>gs for the<br />

<strong>Arctic</strong> tern, both on an <strong>in</strong>ternational scale <strong>and</strong> on a national scale.<br />

The study on <strong>Arctic</strong> tern migration (Manus I) – the longest annual migration<br />

ever recorded <strong>in</strong> any animal – is a study with an <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

appeal. The study documented how Greenl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Icel<strong>and</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>terns</strong> conduct the roundtrip migration to the Weddell Sea <strong>in</strong> Antarctica<br />

<strong>and</strong> back. Although the sheer distance (71,000 km on average) travelled<br />

by the birds is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g, the study furthermore showed how the <strong>terns</strong><br />

depend on high-productive at-sea areas dur<strong>in</strong>g their massive migration.<br />

On the southbound migration, the birds would stop for almost a month<br />

(25 days on average) <strong>in</strong> the central part <strong>of</strong> the North Atlantic Ocean before<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g south. Close to Equator (~10º N) a divide <strong>in</strong> the migration path<br />

way occurred: seven birds migrated along the coast <strong>of</strong> Africa, while four<br />

birds crossed the Atlantic Ocean to follow the coast <strong>of</strong> South America. The<br />

northbound migration from the w<strong>in</strong>ter quarters to the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> grounds<br />

was performed particular fast (520 km per day on average) follow<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

route <strong>of</strong> favourable w<strong>in</strong>d systems.<br />

Included <strong>in</strong> this thesis is also the fi rst quantifi ed estimate <strong>of</strong> the capacity to<br />

produce a replacement clutch <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> (Manus II <strong>and</strong> III). Although<br />

it is <strong>of</strong>ten mentioned <strong>in</strong> the literature that the species will<strong>in</strong>gly relays, this<br />

study is the fi rst where the reproductive response <strong>of</strong> experimentally manipulated<br />

<strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> pairs is monitored. We found that approximately half<br />

(53.3 %) <strong>of</strong> the affected birds would produce a replacement clutch when<br />

the eggs were removed late <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>cubation period. Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, growth<br />

<strong>and</strong> survival rates <strong>in</strong> chicks from these clutches did not differ from chicks<br />

reared four weeks later <strong>in</strong> the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> season, although a shift <strong>in</strong> forag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

pattern <strong>and</strong> prey size was apparent (Manus III).<br />

At a level <strong>of</strong> more national <strong>in</strong>terest, the study produced the fi rst estimates<br />

<strong>of</strong> the key prey species <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. Although zooplankton<br />

<strong>and</strong> various fi sh species were present <strong>in</strong> the chick diet <strong>of</strong> <strong>terns</strong><br />

<strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Disko Bay, Capel<strong>in</strong> (Mallotus villosus) was the s<strong>in</strong>gle most important<br />

prey species found <strong>in</strong> all age groups <strong>of</strong> chicks (Manus III).<br />

The thesis also <strong>in</strong>cludes a study on the fl uctuat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> found <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong><br />

<strong>terns</strong> (Manus IV). Although the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern may show an overall fi delity<br />

to the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> region, our study showed a considerable variation <strong>in</strong> colony<br />

size between years <strong>in</strong> the small <strong>and</strong> mid sized colonies <strong>of</strong> Disko Bay.<br />

These variations were likely to be l<strong>in</strong>ked to local phenomena, such as disturbance<br />

from predators, rather than to large-scale occurr<strong>in</strong>g phenomena.<br />

From the long periods spent <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies it was furthermore<br />

possible to document the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> association between <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

9

Figure 1. An <strong>Arctic</strong> tern nest at<br />

Kitsissunnguit, Disko Bay, <strong>Arctic</strong><br />

West Greenl<strong>and</strong> where fi eldwork<br />

was conducted <strong>in</strong> 2002-2006.<br />

Note the lush vegetation surround<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the nest.<br />

Photo: Carsten Egevang.<br />

10<br />

other <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> waterbirds. In a study conducted on <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> phalaropes<br />

(Phalaropus fulucarius <strong>and</strong> P. lobatus) at Kitsissunnguit (Manus V) a close<br />

behavioural response to tern alarms could be identifi ed. These fi nd<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

imply that the altered distributions <strong>of</strong> waterbirds observed at Kitsissunnguit<br />

were governed by the distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> as<br />

suggested by Egevang et al. (2004).<br />

Included <strong>in</strong> the thesis are furthermore results with an appeal to the Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

management agencies. Along with estimates <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population<br />

size at the two most important <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies <strong>in</strong> West Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> East Greenl<strong>and</strong>, the study produced recommendations on how<br />

a potential future susta<strong>in</strong>able egg harvest could be carried out (Manus II),<br />

<strong>and</strong> on how to monitor <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> (Manus IV).

Dansk resumé<br />

Denne afh<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g præsenterer resultater fra studier udført på havterne<br />

(Sterna paradisaea) i perioden 2002-2008. Data i forb<strong>in</strong>delse med afh<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>gen<br />

er <strong>in</strong>dsamlet gennem feltarbejde på to lokaliteter i Grønl<strong>and</strong>: Kitsissunnguit<br />

(Grønne Ejl<strong>and</strong>), Disko Bugt i arktisk Vestgrønl<strong>and</strong> samt på<br />

S<strong>and</strong>øen i høj-arktisk Nordøstgrønl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Vidensgrundlaget for havternen i Grønl<strong>and</strong> før 2002 var gennemgående<br />

r<strong>in</strong>ge, med aspekter af artens ynglebiologi ubeskrevet for den grønl<strong>and</strong>ske<br />

best<strong>and</strong>s vedkommende. Denne afh<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g præsenterer ny viden for<br />

havternen både på en <strong>in</strong>ternational skala, såvel som på en national skala.<br />

Først og fremmest er studiet af havternens træk (Manus I) – det længste<br />

træk registreret hos noget dyr – et studie med <strong>in</strong>ternational appel. Studiet<br />

dokumenterer hvorledes terner, der yngler i Nordøstgrønl<strong>and</strong> og Isl<strong>and</strong>,<br />

gennemfører trækket til Weddell Havet ved Antarktis, og tilbage igen.<br />

Alene den tilbagelagte distance (gennemsnitlig 71.000 km) er <strong>in</strong>teressant,<br />

men studiet kunne også dokumentere, hvordan ternerne under deres lange<br />

træk er afhængige af havområder med særlig høj biologisk produktion.<br />

På det sydgående træk stopper fuglene trækket og opholder sig i næsten<br />

en måned (25 dage i gennemsnit) i den centrale del af Nordatlanten, før<br />

de fortsætter mod syd. Tæt ved Ækvator (~10º N) opstår en opdel<strong>in</strong>g af<br />

trækvejen: Af 11 mærkede <strong>in</strong>divider fortsætter syv langs Afrikas kyst,<br />

mens fi re <strong>in</strong>divider krydser Atlanten, for at fortsætte langs østkysten af<br />

Sydamerika. Det nordgående træk fra v<strong>in</strong>terkvarteret til ynglepladserne<br />

blev gennemført med særlig høj hastighed (gennemsnitligt 520 km per<br />

dag) og fulgte en rute med favorable v<strong>in</strong>dretn<strong>in</strong>ger.<br />

Denne afh<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>deholder også det første kvantifi cerede estimat af<br />

havternens evne til at producere et såkaldt omlægskuld – et erstatn<strong>in</strong>gskuld<br />

hvis første kuld går tabt (Manus II og III). På trods af, at det <strong>of</strong>te nævnes<br />

i litteraturen at havternen villigt omlægger, er dette studie det første<br />

der overvåger det reproduktive respons på eksperimentalt manipulerede<br />

ynglepar. Vi f<strong>and</strong>t, at omtrent halvdelen (53,3 %) af fuglene producerede<br />

et omlægskuld, når det første kuld blev fjernet i den sidste del af rugeperioden.<br />

Overraskende viste det sig, at vækstrater og overlevelse hos unger<br />

fra omlægskuldene ikke var forskellige fra unger opfostret fi re uger tidligere,<br />

på trods af, at et skifte i både fourager<strong>in</strong>gsmønster og størrelse af<br />

byttedyr kunne identifi ceres (Manus III).<br />

Af mere national <strong>in</strong>teresse producerede studierne i forb<strong>in</strong>delse med afh<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>gen<br />

de første undersøgelser af havternens fødevalg i Grønl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

På trods af at fl ere forskellige fi ske- og zooplanktonarter var til stede i den<br />

føde der blev bragt til ungerne i Disko Bugt, Vestgrønl<strong>and</strong>, viste det sig,<br />

at lodde (Mallotus villosus) var nøglefødearten for alle aldersgrupper af<br />

unger (Manus III).<br />

Afh<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>gen omh<strong>and</strong>ler også et studie af den fl uktuerende yngleforekomst<br />

som forekommer hos havternen (Manus IV). Selv om havternen<br />

udviser en overordnet tr<strong>of</strong>asthed mod yngleregionen, viste vores studier,<br />

at der forekommer en betydelig variation i antallet af ynglefugle i kolonien<br />

mellem sæsonerne i de små og mellemstore kolonier i Disko Bugtområdet.<br />

Disse variationer er s<strong>and</strong>synligvis koblet til lokalt forekommen-<br />

11

Figure 2. An <strong>Arctic</strong> tern nest at<br />

the barren S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>, High-arctic<br />

Northeast Greenl<strong>and</strong>, where<br />

fi eldwork was conducted <strong>in</strong> 2007<br />

<strong>and</strong> 2008.<br />

12<br />

de fænomener, eksempelvis forstyrrelse fra prædatorer, mere end de er<br />

forklaret af forhold der forekommer på større skala.<br />

Gennem de lange perioder, tilbragt i havternekolonierne i forb<strong>in</strong>delse<br />

med feltarbejdet, var det muligt at dokumentere det positive yngleforhold<br />

mellem havterner og <strong>and</strong>re ynglende v<strong>and</strong>fugle. I et studie udført<br />

på ynglende thors- og od<strong>in</strong>shane (Phalaropus fulucarius og P. lobatus) på<br />

Kitsissunnguit (Manus V), kunne et tæt adfærdsmæssigt respons på havternens<br />

advarselskald identifi ceres. Disse resultater s<strong>and</strong>synliggør, at den<br />

observerede ændrede fordel<strong>in</strong>g af svømmesnepper på Kitsissunnguit følger<br />

havternens udbredelse på øerne, som foreslået af Egevang et al. 2004.<br />

Afh<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>gen <strong>in</strong>deholder desuden resultater møntet på de grønl<strong>and</strong>ske<br />

forvaltn<strong>in</strong>gsmyndigheder. Foruden estimater af ynglebest<strong>and</strong>en i de to<br />

vigtigste havternekolonier i Vest- og Nordøstgrønl<strong>and</strong>, præsenteres anbefal<strong>in</strong>ger<br />

til hvordan en fremtidig bæredygtig udnyttelse af havterneægsaml<strong>in</strong>g<br />

kan tænkes udført (Manus II), og konkrete forslag til hvordan<br />

overvågn<strong>in</strong>gen af havternekolonierne i Grønl<strong>and</strong> kan udføres (Manus IV).

Eqikkaaneq<br />

Ilisimatuutut allaatigisaq manna imeqqutaallanik (Sterna paradisaea) 2002-<br />

2008-mi misissu<strong>in</strong>erit <strong>in</strong>erner<strong>in</strong>ik saqqummiussivoq. Allaatigisamut<br />

atatillugu paasissutissat Kalaallit Nunaanni piffi nni marluusuni: Kitsissunnguit,<br />

Qeqertarsuup Tunuani Kitaata issittortaani aamma S<strong>and</strong>øenimi<br />

Tunup avannaani issittorsuarmi, misissuiartornikkut katersorneqarsimapput.<br />

Kalaallit Nunaanni imeqqutaalaq pillugu 2002 sioqqullugu ilisimasanut<br />

tunngaviusut annikitsu<strong>in</strong>naasimapput, pissuseqatigiit nunats<strong>in</strong>ni uumasuusut<br />

k<strong>in</strong>guaassiornikkut pissusaat arlalitsigut nassuiarneqarsimanatik.<br />

Allaatigisaq manna imeqqutaalaq pillugu paasisanik nutaanik nunap iluani<br />

nunallu tamat akornanni nallersuuss<strong>in</strong>naasunik saqqummiussivoq.<br />

Siullertut p<strong>in</strong>gaarnertullu imeqqutaallap <strong>in</strong>gerlaartarnera pillugu misissu<strong>in</strong>eq<br />

(Manus I) – uumasuni tamani <strong>in</strong>gerlaarnerit nalunaarsorneqarsimasut<br />

tannersaat – misissu<strong>in</strong>eruvoq nunat tamat akornanni soqutig<strong>in</strong>aateqartussaq.<br />

Misissu<strong>in</strong>erup nassuiarpaa qanoq imeqqutaallat Tunup<br />

avannaaniit Isl<strong>and</strong>imiillu, Sikuiuitsumi kujallermiittumut Weddelip Imartaanut,<br />

utimullu, <strong>in</strong>gerlaartarnersut. Ingerlaarnerup takissusaa imm<strong>in</strong>i<br />

(agguaqatigiissillugu 71.000 km) soqutig<strong>in</strong>arpoq, misissu<strong>in</strong>erulli aamma<br />

nassuiarpaa, qanoq imeqqutaallat <strong>in</strong>gerlaarnermi nalaanni imartat immikkut<br />

p<strong>in</strong>ngorarfi ulluartut p<strong>in</strong>ngitsoors<strong>in</strong>naanngikkaat. Kujammut <strong>in</strong>gerlaarnerm<strong>in</strong>ni<br />

timmissat qaammat<strong>in</strong>gajammik (agguaqatigiissillugu<br />

ulluni 25-ni) sivisussusilimmik <strong>in</strong>gerlaarnertik unitsittarpaat Atlantikullu<br />

avannaata qiterpasissuani, kujammut <strong>in</strong>gerlaqq<strong>in</strong>ng<strong>in</strong>nerm<strong>in</strong>ni, un<strong>in</strong>ngaartarlutik.<br />

Ækvatorip qanittuani (~10º N) <strong>in</strong>gerlaarnerup aqqutaani<br />

avissaarfeqartarpoq: Nalunaaqutserneqarsimasuni 11-usuni arfi neq<br />

marluk Afrikap s<strong>in</strong>eriaa atuarlugu <strong>in</strong>gerlaqqipput, sisamallu Atlantiku<br />

ikaarlugu Amerikkap kujalliup s<strong>in</strong>eriaa atuarlugu <strong>in</strong>gerlaqqiffi galugu.<br />

Avannamut ukiivimmiit piaqqisarfi mmut <strong>in</strong>gerlaarneq sukkangaatsiartumik<br />

<strong>in</strong>gerlavoq (agguaqatigiissillugu ullormut 520 km) <strong>in</strong>gerlaarfi llu iluaqutaasunik<br />

sammivil<strong>in</strong>nik anoreqarfi usoq atuarsimallugu.<br />

Allaaserisap massuma aamma imarivaa imeqqutaallap mannilioqqiss<strong>in</strong>naaneranik<br />

– piaqq<strong>in</strong>erit/manniliornerit siulliit iluats<strong>in</strong>ngippata mannilioqqiss<strong>in</strong>naaneq<br />

- kisitsis<strong>in</strong>ngorlugu miss<strong>in</strong>gersu<strong>in</strong>erit siullersaat<br />

(Manus II aamma III). Naak allaatigisani imeqqutaallat ajornasaaratik<br />

mannilioqqittarnerarlugit oqaatig<strong>in</strong>iarneqartaraluartut, misissu<strong>in</strong>erup<br />

massuma, aappariit piaqqisut misileraatigalugit uukapaat<strong>in</strong>neqartut<br />

k<strong>in</strong>guaassiornikkut qisuariarnerannik nakkutig<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>nerit siullersaraat.<br />

Paasivarput, timmissat affaasa missaat (53,3 %) ivanerup naggataata tungaani<br />

manniliaat peerneqaraangata mannilioqqittartut. Tupaallannartumik<br />

paas<strong>in</strong>arsivoq, piaqqat mannilioqq<strong>in</strong>nerniit tukersimasut alliartornerat<br />

umaannars<strong>in</strong>naanerallu piaqqanit sapaatit akunner<strong>in</strong>i sisamani<br />

sius<strong>in</strong>nerusukkut allisarsimasun<strong>in</strong>ngarnit allaanerunngitsut, naak, ner<strong>in</strong>iarnikkut<br />

p<strong>in</strong>iagaasalu angissusiisigut allaanerussutit ilisar<strong>in</strong>eqars<strong>in</strong>naasimagaluartut<br />

(Manus III).Nunap iluani soqutig<strong>in</strong>aateqarnertut allaatigisamut<br />

atatillugu imeqqutaallat Kalaallit Nunaanni ner<strong>in</strong>iartagaannik<br />

misissu<strong>in</strong>erit siulliit suliar<strong>in</strong>eqarput. Naak aalisakkat uumasuaqqallu<br />

iker<strong>in</strong>narsiortut assigi<strong>in</strong>ngitsut arlallit Kitaani, Qeqertarsuup Tunuani<br />

piaqqanut apuunneqartartunut ilaagaluartut, paas<strong>in</strong>arsivoq ammassak<br />

(Mallotus villosus) piaqqani tamanik angissuseqartuni nerisassat p<strong>in</strong>gaarnersarigaat<br />

(Manus III).<br />

13

Figure 3. Map <strong>of</strong> study areas<br />

where fi eld work <strong>in</strong> the thesis<br />

were conducted. Inset map <strong>in</strong> upper<br />

left corner shows the location<br />

<strong>of</strong> A) Kitsissunnguit <strong>in</strong> Disko Bay<br />

<strong>and</strong> B) <strong>of</strong> S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Northeast<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong>. The map scale<br />

(lower right corner) applies to<br />

both A <strong>and</strong> B<br />

14<br />

Allaatigisami aamma samm<strong>in</strong>eqarput imeqqutaallat piaqqiortartut amerlassutsimikkut<br />

ilaatigut allanngorartarnerisa, misissuiffi g<strong>in</strong>eqarnerat<br />

(Manus IV). Naak imeqqutaalaq piaqqisarfi mm<strong>in</strong>ut amerlanertigut aalajaattaraluartoq,<br />

misissu<strong>in</strong>itta takutippaat, Qeqertarsuup Tunuani piaqqisarfi<br />

nni m<strong>in</strong>nerni akunnattunilu timmissat piaqqisut piaqq<strong>in</strong>ermiit piaqq<strong>in</strong>ermut<br />

malunnaatilimmik allanngorartut. Allanngorarnerit tamakku<br />

piffi mmi annikitsumi pisunut attuumassuteqarnissaat ilimanaateqarput,<br />

assersuutigalugu kiisortunit akornusersorneqarneq, piffi mmilu annertunerusumi<br />

pisut nassuiaataas<strong>in</strong>naanerat ilimanaateqanng<strong>in</strong>nerulluni.<br />

Imeqqutaalaqarfi nnut misissuiartortarnerni sivisoqisuni, imeqqutaallat<br />

timmissallu naluusillit piaqqisut allat imm<strong>in</strong>nut iluaqusersoqatigiittarneri<br />

nalunaarsorneqars<strong>in</strong>naasimapput. Naluumasortut Kajuaqqallu<br />

(Phalaropus fulucarius aamma P. lobatus) piaqqisut Kitsissunnguani misissuiffi<br />

g<strong>in</strong>erisigut (Manus V), imeqqutaallat kalerrisaar<strong>in</strong>er<strong>in</strong>ut qisuariaatit<br />

ersarissut ilisar<strong>in</strong>eqars<strong>in</strong>naasimapput. Inernerit taakkua qularnaallisippaat,<br />

naluumasortukkut Kitsissunnguani siammarsimaffi mmikkut<br />

allannguutaasa imeqqutaallat qeqertani sumi<strong>in</strong>neri malittarigaat, soorlu<br />

Egevang et al. 2004-mi siunnersuutig<strong>in</strong>eqarsimasoq.<br />

Allaatigisap aamma imarai <strong>in</strong>ernerit Kalaallit Nunaanni oqartussanut<br />

saaffi g<strong>in</strong>nittut. Kitaani Tunullu avannaani imeqqutaalaqarfi nni p<strong>in</strong>gaarnerpaani<br />

piaqqisut amerlassusaannik miss<strong>in</strong>gersu<strong>in</strong>erit saniatigut, siunissami<br />

piujuartitsilluni imeqqutaallanik manissarluni atuis<strong>in</strong>naanermik<br />

<strong>in</strong>assuteqaatit saqqummiunneqarput (Manus II), Kalaallillu Nunaanni<br />

imeqqutaalaqarfi it nakkutig<strong>in</strong>eqars<strong>in</strong>naanerannut tigussaasunik siunnersuuteqartoqarluni<br />

(Manus IV).

1 Synopsis<br />

1.1 Introduction<br />

There are several compell<strong>in</strong>g reasons to study the migration <strong>and</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. From a global perspective, the<br />

<strong>Arctic</strong> tern is the very epitome <strong>of</strong> long-distance migration <strong>in</strong> birds, <strong>and</strong><br />

no other animal species connects the two Polar Regions, as the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern<br />

does. Thus, the study <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> tern migration is not only an exam<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

<strong>of</strong> migrat<strong>in</strong>g animals at the edge <strong>of</strong> their physical performance, it is also an<br />

exploration <strong>of</strong> a species mov<strong>in</strong>g through a vast proportion <strong>of</strong> the world’s<br />

mar<strong>in</strong>e areas <strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle calendar year, experienc<strong>in</strong>g a rapidly chang<strong>in</strong>g<br />

environment with altered forag<strong>in</strong>g opportunities on both the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g grounds.<br />

At a local scale, no other bird species <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> encapsulates the feel<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>of</strong> summer <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong>. The cry <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern is for many <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

the ultimate sign <strong>of</strong> the end <strong>of</strong> a long w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>and</strong> the onset <strong>of</strong> summer,<br />

the return <strong>of</strong> the sun <strong>and</strong> warmer temperatures. Although tern eggs<br />

are small <strong>and</strong> may not contribute much as a source <strong>of</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>, the habit <strong>of</strong><br />

harvest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Arctic</strong> tern eggs <strong>in</strong> summer has a long tradition <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>,<br />

<strong>and</strong> is considered one <strong>of</strong> the highlights <strong>of</strong> the summer season. There is no<br />

doubt that, to the people <strong>of</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>, the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern has a special status<br />

amongst birds.<br />

From a more scientifi c po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view, the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to study<br />

due to its obvious appearance on the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> the placement <strong>of</strong><br />

its nest directly on the ground. This makes the species relatively easy to<br />

study, compared with many other seabird species, where the nest is concealed<br />

<strong>in</strong> a rocky crevice or burrow, or on rocky ledges <strong>of</strong> high steep cliffs.<br />

Furthermore, the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern is a surface feeder <strong>and</strong> only capable <strong>of</strong> forag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> the top half meter <strong>of</strong> the water column. Theoretically, this twodimensional<br />

feed<strong>in</strong>g niche makes the species more vulnerable to changes<br />

<strong>in</strong> prey availability, <strong>and</strong> a direct response <strong>in</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> performance can be<br />

detected with<strong>in</strong> a <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> season.<br />

From an environmental management perspective, the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

because <strong>of</strong> its function as a “biodiversity generator”. Smaller species,<br />

such as shorebirds, apparently benefi t from the agonistic behaviour<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> densities <strong>of</strong> other species are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten found with<strong>in</strong> the boundaries <strong>of</strong> an <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colony (Nguyen et al.<br />

2006, Egevang et al. 2008, Egevang et al. 2004, Egevang et al. 2006).<br />

The Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources generates specifi c knowledge<br />

on the Greenl<strong>and</strong> mar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> terrestrial fauna to provide the Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

Government with management advice on the susta<strong>in</strong>able use <strong>of</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

resources. In Greenl<strong>and</strong>, there is a long traditional <strong>of</strong> bird harvest<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

<strong>and</strong> research on seabirds has ma<strong>in</strong>ly focused on the two most harvested<br />

species, Brünnich’s Guillemot (Uria lomvia) <strong>and</strong> Common Eider (Somateria<br />

mollissima), with little attention directed towards other harvested species,<br />

such as the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern. As monitor<strong>in</strong>g programmes for guillemots <strong>and</strong> eiders<br />

developed over the last decade, opportunities to exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g research<br />

activities <strong>of</strong> GINR (to species like little auks, black-legged kittiwakes, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong>) arose.<br />

15

16<br />

1.2 Objectives<br />

Aim <strong>of</strong> the thesis: The <strong>in</strong>itial aims <strong>of</strong> <strong>and</strong> motivations for my research<br />

were to illum<strong>in</strong>ate a number <strong>of</strong> issues regard<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong><br />

tern <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>, particularly from a management perspective. Basic<br />

questions, like “What is the current status <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population<br />

<strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> ?”, “What is the key prey species for <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

?” <strong>and</strong> “Do <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> relay <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> ?” were unanswered. Later<br />

<strong>in</strong> the process, technological advances rapidly reduced the mass <strong>of</strong> geolocators,<br />

<strong>and</strong> allowed the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern to be targeted as a study subject, <strong>and</strong><br />

the focus <strong>of</strong> my research broadened to also <strong>in</strong>clude this aspect.<br />

Aim <strong>of</strong> the synopsis: The aim <strong>of</strong> this synopsis is to present background<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on the <strong>biology</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern <strong>and</strong> highlight how the results<br />

<strong>of</strong> this work have contributed to an improved underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> this<br />

species, either globally or specifi cally <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. In this context, the<br />

synopsis also <strong>in</strong>cludes results generated dur<strong>in</strong>g the course <strong>of</strong> my research,<br />

but not presented <strong>in</strong> the manuscripts – especially those relat<strong>in</strong>g to issues<br />

specifi c to Greenl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

1.3 Distribution<br />

The <strong>Arctic</strong> tern has a circumpolar distribution between the Boreal <strong>and</strong><br />

High <strong>Arctic</strong> zones. The <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> range <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> is large (more than<br />

350,000 km 2 ), <strong>and</strong> the species is found <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a variety <strong>of</strong> habitats.<br />

In Greenl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> are found <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> throughout the country. In<br />

West Greenl<strong>and</strong>, the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern shows a patchy distribution with large<br />

gaps evident. The core <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> areas are <strong>in</strong> Disko Bay <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> Upernavik<br />

District (Boertmann et al. 1996, Egevang <strong>and</strong> Boertmann 2003). In East<br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong>, the colonies are fewer, more scattered, <strong>and</strong> smaller than <strong>in</strong><br />

West Greenl<strong>and</strong>. Typically, colonies <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> are found at small, isolated<br />

islets along the coast, <strong>and</strong> range from a few tens <strong>of</strong> pairs to a few<br />

hundred pairs. Large colonies <strong>of</strong> more than 2,000 pairs are rare, <strong>and</strong> even<br />

solitary <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> has been recorded <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> (Boertmann 1994).<br />

1.4 Population status <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

The total world population <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> is estimated at 1 to 2 million<br />

pairs (Lloyd et al. 1991). Global estimates <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population are<br />

rough, however, <strong>and</strong> some large populations (e.g. <strong>in</strong> Russia <strong>and</strong> Alaska<br />

are diffi cult to estimate (Wetl<strong>and</strong>s International 2006).<br />

Prior to 2002, there was little effort to monitor the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population<br />

<strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>. Counts were opportunistic <strong>and</strong> only performed <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

years. The total <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> is estimated to <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

at least 65,000 pairs (Egevang <strong>and</strong> Boertmann 2003), but limited data<br />

is available. However, three studies provide <strong>in</strong>formation that can be used<br />

to address population status: Salomonsen (1950) visited Kitsissunnguit,<br />

the largest <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colony <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>, for a short (1 ½ day) period <strong>in</strong><br />

1949, <strong>and</strong> estimated the population to be 100,000 pairs. This high number<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> birds has never been encountered aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> censuses conduct-

ed between 1980 <strong>and</strong> 2009, where estimates range from 0 to 25,000 pairs<br />

(Kampp 1980, Frich 1997, Hjarsen 2000, Egevang et al. 2004, Manus IV).<br />

Burnham et al. (2005) revisited <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies censured <strong>in</strong> Uummannaq<br />

District by Berthelsen (1921) <strong>in</strong> the period 1905 to 1920, to fi nd that<br />

population numbers had decl<strong>in</strong>ed to less than one-third between counts.<br />

Egevang <strong>and</strong> Boertmann (2003) compared <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colony counts <strong>in</strong><br />

the Greenl<strong>and</strong> Seabird Colony Database (GSCD) between 1921 <strong>and</strong> 2002,<br />

<strong>and</strong> concluded that a long-term decl<strong>in</strong>e was present, but the population<br />

seemed to stabilize <strong>in</strong> more recent counts, between 1986 <strong>and</strong> 2002.<br />

Although the above studies provide only circumstantial evidence <strong>of</strong> a decl<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

it seems reasonable to conclude that the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population <strong>in</strong><br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong> has undergone a decl<strong>in</strong>e s<strong>in</strong>ce the middle <strong>of</strong> the last century.<br />

However, the magnitude <strong>of</strong> this decl<strong>in</strong>e is diffi cult to quantify <strong>and</strong> attempts<br />

to estimate the historical population size should be treated with caution.<br />

The <strong>Arctic</strong> tern is categorized as “near threatened” <strong>in</strong> the Greenl<strong>and</strong> Red<br />

List (Boertmann 2007).<br />

1.5 Population status at Kitsissunnguit<br />

The <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population at Kitsissunnguit has been followed with special<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest by both managers <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational, non-government<br />

environmental organisations. The archipelago is home to one <strong>of</strong><br />

the largest <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies <strong>in</strong> the world, <strong>and</strong> has been designated both<br />

as a Ramsar site, a special protected area for <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> birds <strong>in</strong> national<br />

legislation, <strong>and</strong> an Important Bird Area (IBA). Despite these designations,<br />

there was little effort to monitor the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population <strong>in</strong> a systematic<br />

way prior to 2002. The sparse historical <strong>in</strong>formation on population size<br />

available from Kitsissunnguit <strong>in</strong>dicated a crash <strong>in</strong> the population, with<br />

numbers go<strong>in</strong>g from 100,000 pairs <strong>in</strong> 1949 (Salomonsen 1950) to no <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

birds <strong>in</strong> 2000 (Hjarsen 2000), <strong>and</strong> a great concern arose with<strong>in</strong> government<br />

<strong>and</strong> non-governmental <strong>in</strong>stitutions.<br />

The Greenl<strong>and</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> National Resources <strong>in</strong>troduced a modifi ed distance<br />

sampl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e transect method to estimate population size at<br />

Kitsissunnguit <strong>in</strong> 1996 (Frich 1997), <strong>and</strong> annual counts were performed<br />

between 2002 <strong>and</strong> 2006 (Manus IV). This series <strong>of</strong> consecutive population<br />

estimates showed that the <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> at Kitsissunnguit had not suffered<br />

a complete population crash, <strong>and</strong> found <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> numbers to be relatively<br />

stable between 15,000 <strong>and</strong> 22,000 pairs (Manus IV). Although these estimates<br />

are not <strong>in</strong> the same magnitude as the former estimate by Salomonsen<br />

<strong>in</strong> the mid 20th century, it is with<strong>in</strong> the same magnitude as the<br />

estimate <strong>of</strong> roughly 25,000 pairs by Kampp et al. <strong>in</strong> 1980.<br />

1.6 Fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

The <strong>Arctic</strong> tern is <strong>of</strong>ten referred to as a species with fl uctuat<strong>in</strong>g colony<br />

attendance, large variation <strong>in</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> numbers, <strong>and</strong> years <strong>of</strong> skipped<br />

<strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (Manus IV). Breed<strong>in</strong>g site fi delity at a regional level is high <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong>, but dispersal to neighbour<strong>in</strong>g <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> colonies occurs frequently<br />

(Devl<strong>in</strong> et al. 2008, Møller et al. 2006, Br<strong>in</strong>dley et al. 1999, Ratcliffe<br />

17

18<br />

2004). Although poorly understood <strong>and</strong> documented <strong>in</strong> the literature, it<br />

is important to address whether variations <strong>in</strong> colony size may be caused<br />

by locally occurr<strong>in</strong>g phenomena, such as predation <strong>and</strong> disturbance, or if<br />

these variations are l<strong>in</strong>ked to large scale events, such as food availability<br />

or climatic variations. In order to make sense <strong>of</strong> counts at <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies<br />

where variation occurs, it is important to underst<strong>and</strong> the scale (from<br />

with<strong>in</strong>-colony to regional scale) at which variations <strong>in</strong> colony attendance<br />

occur. A particular comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> factors makes it diffi cult to address<br />

population size, status, <strong>and</strong> trends <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> (Ratcliffe 2004). This is<br />

most pronounced <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Arctic</strong> zone where <strong>Arctic</strong> tern <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> sites may<br />

be diffi cult to access <strong>and</strong> colonies can be widely distributed.<br />

In addition to estimates <strong>of</strong> population size from the two study sites, Kitsissunnguit<br />

(2002-2006) <strong>and</strong> S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong> (2006-2009), it was possible to conduct<br />

annual counts <strong>in</strong> 14 <strong>Arctic</strong> tern colonies <strong>in</strong> the southern part <strong>of</strong> Disko<br />

Bay (the Akunnaaq area) <strong>in</strong> the period 2002-2005 (Manus IV). Considerable<br />

fl uctuation was found between years <strong>in</strong> these small <strong>and</strong> mid-sized<br />

colonies (mean CV <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual colonies equalled 117.5 %), whereas the<br />

colonies at Kitsissunnguit only showed m<strong>in</strong>or annual variation (47.4 % at<br />

sub-colony level, 14.6 % at overall level). When comb<strong>in</strong>ed, however, the<br />

total population size <strong>of</strong> the Disko Bay colonies (more that 80 % <strong>of</strong> the Artic<br />

tern colonies <strong>in</strong> Disko Bay), varied little (CV 6.7 %), <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g local<br />

movements between the colonies <strong>and</strong> that annual variation was l<strong>in</strong>ked to<br />

locally occurr<strong>in</strong>g phenomena.<br />

Variation at high-arctic S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong> was even more pronounced, with complete<br />

<strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> failures recorded <strong>in</strong> two out <strong>of</strong> four seasons (Manus IV).<br />

1.7 Plausible cause <strong>of</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> population size<br />

<strong>Arctic</strong> tern populations <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> are affected by numerous factors regulat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

population size <strong>and</strong> the observed long-term decl<strong>in</strong>e is likely to be<br />

caused by more than one factor. <strong>Arctic</strong> foxes (Alopex lagopus) are known to<br />

cause devastat<strong>in</strong>g predation when they are able to access a colony (Bianki<br />

<strong>and</strong> Isaksen 2000, Manus IV), <strong>and</strong> multiple avian predators are known to<br />

depredate egg, chicks, <strong>and</strong>, to a lesser degree, adult <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> (Cramp<br />

1985, Hatch 2002). Although these predators have always been present <strong>in</strong><br />

Greenl<strong>and</strong>, local Inuit claim that the number <strong>of</strong> predators <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

has <strong>in</strong>creased, caus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>terns</strong> to decl<strong>in</strong>e. Although the relationship between<br />

food availability <strong>and</strong> reproductive performance <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

is poorly documented, the study on chick diet <strong>and</strong> chick survival at<br />

Kitsissunnguit (Table 2, Manus III) <strong>in</strong>dicates that productivity is low compared<br />

with other studies abroad (Appendix I <strong>in</strong> Hatch 2002). Food shortage<br />

or <strong>in</strong>accessibility <strong>of</strong> suitable prey items can occur <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> waters<br />

<strong>and</strong> may affect the ability <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> to reproduce <strong>in</strong> some years.<br />

In Greenl<strong>and</strong>, harvest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> tern eggs for consumption has probably<br />

taken place as long as humans have <strong>in</strong>habited the country (Manus II).<br />

The impact <strong>of</strong> this harvest<strong>in</strong>g was <strong>in</strong>itially constra<strong>in</strong>ed by a small human<br />

population size <strong>and</strong> limited forms <strong>of</strong> transportation. The human population<br />

<strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> has more than quadrupled s<strong>in</strong>ce the 1950’s (Fægteborg<br />

2000), however, <strong>and</strong> the number <strong>and</strong> size <strong>of</strong> motorized boats has <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

rapidly, allow<strong>in</strong>g greater mobility, <strong>and</strong> likely <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g pressure on the<br />

<strong>Arctic</strong> tern population.

The extent <strong>of</strong> the annual egg harvest <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>s undocumented,<br />

although a few references may provide <strong>in</strong>dications <strong>of</strong> its magnitude:<br />

Salomonsen (1950) estimated the annual harvest at Kitsissunnguit to be<br />

as high as 100,000 eggs, while Frich (1997) estimated that 150-200 persons<br />

visited the archipelago between 6 <strong>and</strong> 25 June 1996, <strong>and</strong> harvested between<br />

3,000 <strong>and</strong> 6,000 eggs. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2002, the level <strong>of</strong> (illegal) harvest<strong>in</strong>g has<br />

decl<strong>in</strong>ed at Kitsissunnguit (pers. obs.).<br />

Conservation concerns for the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> led to<br />

an altered manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the resource: from an open season for egg harvest<br />

until 1 July before 2001, a ban on <strong>Arctic</strong> tern harvest<strong>in</strong>g was <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong><br />

2002. Egg harvest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong> is very much a cultural activity, where<br />

several generations participate <strong>in</strong> gather<strong>in</strong>g eggs dur<strong>in</strong>g summer. The ban<br />

on <strong>Arctic</strong> tern egg harvest<strong>in</strong>g has been met by opposition <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong><br />

where some even consider it a violation <strong>of</strong> basic human rights. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2002,<br />

there has been a considerable pressure on national politicians to re-open<br />

the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern egg harvest season <strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

A harvest <strong>of</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> tern eggs is also carried out <strong>in</strong> Icel<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong>, apparently,<br />

this is conducted without an adverse effect on the population. The egg<br />

harvest <strong>in</strong> Icel<strong>and</strong> differs from the Greenl<strong>and</strong> harvest <strong>in</strong> several ways: <strong>in</strong><br />

Icel<strong>and</strong> the season closes on 15 June, the harvest is only conducted by private<br />

l<strong>and</strong>owners, <strong>and</strong> a high degree <strong>of</strong> predator control (foxes, gulls, <strong>and</strong><br />

ravens) takes place (Aevar Petersen pers. com.).<br />

The outcome <strong>of</strong> a model deal<strong>in</strong>g with egg harvest<strong>in</strong>g at Kitsissunnguit<br />

(Manus II) <strong>in</strong>dicates that a fairly high number <strong>of</strong> eggs could be removed<br />

from the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> population each year as long as egg harvest<strong>in</strong>g is only<br />

conducted early <strong>in</strong> season. The model predicted 7 June as a date for harvest<br />

closure – the date where 92% <strong>of</strong> the maximum number <strong>of</strong> eggs would<br />

be available to harvesters, but the impact on productivity would be m<strong>in</strong>or.<br />

The highest number <strong>of</strong> eggs could be harvested on 16 June, whereas harvest<br />

until 22 June would negatively affect population productivity. Based<br />

on the results <strong>of</strong> the model, high effort egg harvest<strong>in</strong>g until 1 July (as was<br />

the case prior to 2002), is very likely to have placed an unsusta<strong>in</strong>able pressure<br />

on the population, <strong>and</strong> could very well expla<strong>in</strong> the observed decl<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

1.8 Renest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong><br />

In order to address the impact <strong>of</strong> egg harvest<strong>in</strong>g on the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern population<br />

<strong>in</strong> Greenl<strong>and</strong>, basic parameters <strong>of</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>biology</strong> are required<br />

for the species. Although the <strong>Arctic</strong> tern is <strong>of</strong>ten mentioned as a species<br />

that will<strong>in</strong>gly produces a replacement clutch if the fi rst clutch is lost (e.g.<br />

depredated or fl ooded) this is <strong>in</strong> fact very poorly described <strong>in</strong> the literature.<br />

The only scientifi c reference to my knowledge relat<strong>in</strong>g to relay<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> is a paper by Bianki (1967) <strong>in</strong> Russian, quoted by Cramp<br />

(1985) <strong>and</strong> Hatch (2002), show<strong>in</strong>g that relay<strong>in</strong>g only occurs if eggs are lost<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the fi rst 10 days <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>cubation period. Cramp (1985) also states<br />

(without references) that relay<strong>in</strong>g ma<strong>in</strong>ly takes place at lower latitudes,<br />

but is “unlikely <strong>in</strong> the high <strong>Arctic</strong>”. Population dynamic parameters (such<br />

as 1) what proportion <strong>of</strong> the population will relay, 2) at what stage <strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>in</strong>cubation period relay<strong>in</strong>g will occur, <strong>and</strong> 3) growth <strong>and</strong> survival rates <strong>of</strong><br />

chicks orig<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g from replacement clutches), rema<strong>in</strong> largely unknown<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong>.<br />

19

20<br />

Renest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> was an important component <strong>in</strong> the fi eldwork at<br />

Kitsissunnguit (Manus II <strong>and</strong> III). By experimentally remov<strong>in</strong>g eggs <strong>and</strong><br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g the response <strong>of</strong> the <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> birds, the fi rst estimates <strong>of</strong> relay<strong>in</strong>g<br />

rate, <strong>and</strong> chick growth <strong>and</strong> survival rates were obta<strong>in</strong>ed for <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong><br />

(Manus III). However, this challenge was not without large logistical diffi<br />

culties. The lay<strong>in</strong>g date <strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Disko Bay varied (see<br />

section “Variation <strong>in</strong> <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> phenology”) by as much as three weeks,<br />

mak<strong>in</strong>g the onset <strong>of</strong> fi eldwork diffi cult to plan. If <strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>terns</strong> were to<br />

be followed from early <strong>in</strong>cubation, <strong>and</strong> egg removal experiments allow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the birds to mate, egg formation to take place, an <strong>in</strong>cubation period <strong>of</strong> 22<br />

days, <strong>and</strong> chicks were to be followed until fl edg<strong>in</strong>g, the fi eld season had<br />

to be <strong>of</strong> two to three months <strong>in</strong> duration. In practice, the dem<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> such<br />

a long fi eld period proved diffi cult to meet, <strong>and</strong> not all aspects <strong>of</strong> renest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Arctic</strong> <strong>terns</strong> could be covered with<strong>in</strong> the framework <strong>of</strong> this research.<br />

Despite the fact that eggs were removed <strong>in</strong> the latter half <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>cubation,<br />